Kishlak Ma'dan, Upper Euphrates

May 9, 1920

Well, here we are at the next station, the one that was 19 miles away when I stopped writing last night. I turned out at three o’clock this morning. It was bright moonlight and pretty cold. I called Ali and Sa’aleh (Ibrahim) the new servant and got them started making tea, having first called the drivers. I then took a lively run up and down the long flat roof of the khan in my BVDs, while the stolid drivers below, seeing the white ghost prancing on the roof in the moonlight, thought I was crazy, and have eyed me askance ever since. They were very sore at having been roused so early, and said they would be ready in two hours. And do you know, in spite of all I could do, they were right. It was 5 A.M. when we filed slowly out of the khan court. As you know, a khan is simply a large court with covered sheds or stables along three sides, and rooms in two stories along the fourth. We slept very comfortably in our field beds in one of the upper rooms and did not find any vermin, though I expected to be overrun with unspeakable things. Of course there is no furniture of any kind, — simply the bare room; but there is a fireplace for cooking, and Ali was able to prepare our dinner there over a wood fire. We paid 6 rupees for the use of the place and for the wood we burnt. That was about $3 or 60 cents per person, leaving out the caravan!

El Hammam, Upper Euphrates, Saturday Afternoon, May 9, 1920.

Hammam: The Khan with native wagons at the entrance. (N. 3876, P. 7436)

Hammam: The Khan with native wagons at the entrance. (N. 3876, P. 7436)

A pig-stye would be palatial beside the filthy hole in which we are preparing to spend the night! Nothing I have ever seen approaches it. Our life in the Sudan was luxury and cleanliness compared with it. We have an English report on the Baghdad-Aleppo route, made early in the war. At this point the report has the words “Bad khan, 1918”. We would like to add, “Worse, 1920”. I will not go into details. We have had a long rough hot day. The stage of thirty miles assigned for today allowed a little more sleep and we did not turn out until 4:30. At five, old Sheikh Suwan appeared at my door all ready to go. It was tough. We had to find a place for him in one of our wagons, and to put him in a baggage wagon with the driver would have mortally offended all the Arabs of this place. He had brought with him just at our dinner hour last night, the mudir of the village, and a lot of other notables, to ask us to see that he was looked after for he is an old man. These pre-war Turkish carriages are made for orientals, sitting as they are accustomed to sit, on the floor. The owner furnishes some rugs and cushions, and by adding some of your own bedding, you can lie down at any angle and make yourself really quite comfortable. The rough road, however, keeps knocking you about very violently, and the trip is a pretty rough business when kept up day after day.

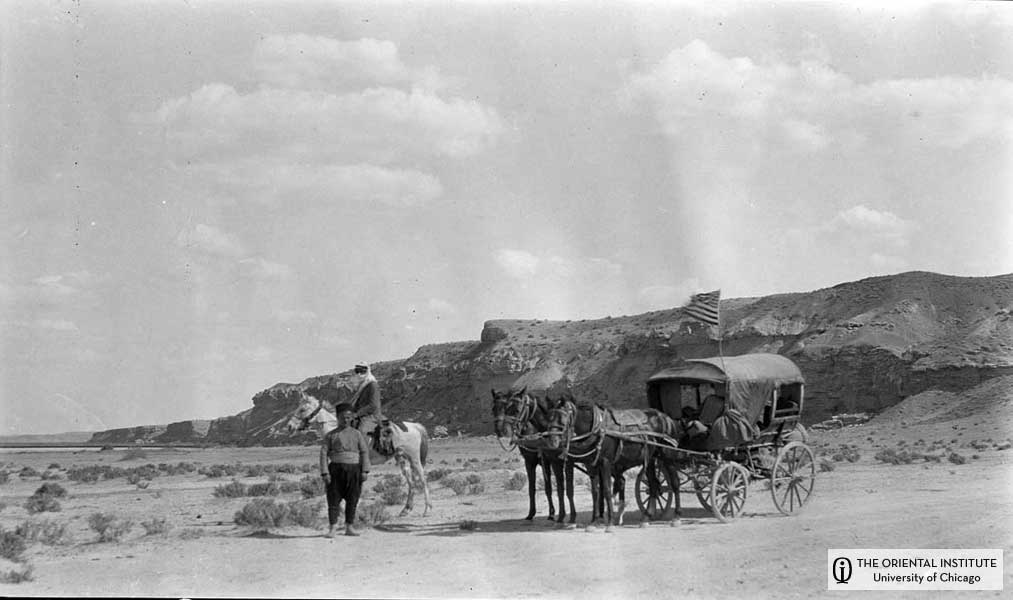

Tibni: View looking to the Euphrates from the cliffs. Wagon of University of Chicago party and an Arab escort in the foreground. (N. 3300, P. 6860)

Tibni: View looking to the Euphrates from the cliffs. Wagon of University of Chicago party and an Arab escort in the foreground. (N. 3300, P. 6860)

We condensed as best we could. Luckenbill and I had stretched out side by side and found the situation very tolerable. The passengers who paid no fare kept entirely out of sight, but were much in evidence notwithstanding. Nevertheless we cultivated a philosophical state of mind, and got on very well, exchanging sympathetic experiences as one or the other of us succeeded in catching one! But with the old Sheikh to provide for, further condensation was impossible. We finally took some things off the front seat beside the driver, put them behind with me, while the room still remaining beside me, was assigned to the sheikh, poor Luckenbill taking to the front seat with the driver. And so we drove off, amid the most hearty salaams of the villagers who gathered about to bid their sheikh farewell. The old chap of course sat cross legged, and as soon as the rough road began, he gradually spread over the whole place and spilled around promiscuously. When his knees were not in my ribs, he was sitting on the type-writer, or in the lunch basket. This is amusing when you write it, but for nine, hot, dusty hours it loses its amusing aspect. At present the old chap sits at my side, and will have to be given room to sleep on the floor beside me, for the entire khan is full. So he has wandered in, and I have just saved my field bed from being completely wrecked by his sitting on it. You know how fragile an X-bed is, and I have given him a seat therefore on a duffle bag, where he is contemplating the type writer with much curiosity. At my other elbow sits his nephew, a fine looking boy of fifteen, who is accompanying his uncle to Aleppo. This is protection with a vengeance! Rather more than we anticipated. I find my apprehensions, as I felt them before we entered the Arab territory, rather diverting. There is not a shadow of danger! Americans may travel where they like in Arabia, for the Arabs know we are not looking for some advantage out of them. I think an Englishman would be in the greatest danger, if he sat where I do at this moment; and a Frenchman still more so. But there is no danger for an American. Everywhere I hear the same words from the Arabs: “The Arabs love the Americans, and we would like to live with them like brothers. We hope they will come here and help us”. The only thing that might happen to us might be a chance meeting with highwaymen who would rob us. But I have heard of similar occurrences in various parts of civilized America according to the best of my recollection.

As we left Sabkha this morning we ran into my suit-case roosting in the road all by itself. Bad loading! Though I have tried my best to systematize the work, even making out a list of each man’s duties, I have ridden in the dust all day behind the baggage wagons to see that we lose nothing. The suit-case was found a second time dangling over the side of the wagon and banging against the wheels. A few miles out of town we passed a large group of Bedwin tents a hundred rods from the highway. “My tents!” said Sheikh Suwan, “come in and have something to eat”. But the boys were a half mile away, leading the caravan, and I told the sheikh it was impossible. Presently the handsome boy whom the sheikh introduced as his nephew, appeared running beside the arabanah, and told us with great glee that he was going to Haleb (Aleppo) with his uncle. The old man sent him over to the tents to direct them to follow with food for his journey. An hour later we stopped to feed and water the horses at a group of huts, which the sheikh said was called Mazar. Here his territory ended, having stretched all the way from Tibni, a stately domain for an Arab sheikh. At Mazar I asked the women to bring out some milk, and although very hardened to dirt by this time, I could not down more than a single cup of the filthy stuff. At this juncture a fine looking Arab in splendid attire, with a brand new Mauser rifle, was introduced by the sheikh as his son, and he added, “He has come riding after you to see you safely out of our land and to wish you safety and health.” The son, Rakaan ibn Suwan by name, at once gave us a very cordial greeting, with the expressions regarding America to which we have now grown accustomed. They all have the same curious gesture which they use to express the relations between the Arabs and America. They hold up one first finger with the thumb turned in toward the palm, and then doing the same with the other hand, they lay the two first fingers together and say: “Thus are the Americans and the Arabs side by side as brothers”. The sheikh asked me why no American rifles had ever appeared in Arabia, although the Americans do everything by machinery. I went to the arabanah and took down the type-writer while a crowd of curious Arabs gathered about. Taking a sheet from my note book I wrote the name Rakaan and gave it to him. But he said at once I must also write my own name with his, which of course I did, and he put the sheet carefully away in his mantle. They were much interested to know that the Americans wrote in this way; but they were still more astonished when I told them there were houses in America with forty windows, one above the other! Many were the grunts and the “By Allahs”, which greeted this information. Rakaan assured me that if any Americans ever came that way again, he would be at their service without reserve, and so with many an “In peace”, and “In the safety of Allah!”, we left Rakaan looking after his father, whose hand he had demonstratively kissed and laid against his own forehead as we drove away.

The river plain all along this region from Sabkha up to El-Hammam is wider than in the Hît to Anah region. A small nation is thinkable in this region, and indeed on the opposite (left) bank of the river, at the mouth of its northern tributary, the Balikh, there are extensive ruins of an ancient town, which has never been more than cursorily examined. At present the place is called Rakka, and fine Neo-Persian blue-glazed bowls are found there and sold by the European antiquity dealers. We were sorry that we could not cross and examine these ruins, but the other side of the river is very unsafe.

I wish I knew more about natural features of the earth. The botany of this region, of course, is beyond me. I get no further than the tamarisks and a few flowers, — the latter being thus far very scanty. Indeed the rolling desert wilderness of northern Arabia, which in this region merges into the Syrian desert, is very barren, — more so than I had anticipated. The withered vegetation of a greenish brown hue, merging into yellow, stretches far across the desolate hills, with a strangely monotonous aspect. I have seen no Bedwin tents on the plateau, and although it is only the first of May, and the winter rains have but just ceased to fall as you have noted in my letters, the ground is parched and dusty, and the grass withered and brown. All the Bedwin are down on the river plain near the shores of the Euphrates. The color of the soil in the valley or on the river plain below is exactly the same as that of the desert plateau above. This color is difficult to describe. It is a dusty and faded terra cotta, just the color of Missouri river water in flood time. There is no contrast therefore as in Egypt, between the tawny desert and the rich black loam of the flood plain. Indeed, I have thus far not seen a single square foot of black soil in Babylonia, Assyria, or Western Asia anywhere. All the soil, even the most rich and productive in Babylonia, displays the same light color, which we in America would at once misjudge as a very poor clayey soil.

A few miles above Sabkha, the road rose along the face of the cliffs, and to our surprise we had immediately below us a river of beautiful clear blue water, filled with fish, some of large size, with numerous turtles basking along the shores. Above us was the steep wall of the rugged cliffs and below us a wall of rock almost as steep, dropping sheer to the water. We went along thus for about a mile. What we had below us was a lake lying in an old and abandoned channel of the river. We would have given much for a bath in this attractive clean water, the first we have seen since early in March.

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577