Palace Hotel, Damascus, Syria

May 29, 1920

Damascus: King’s residence. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8186)

Damascus: King’s residence. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8186)

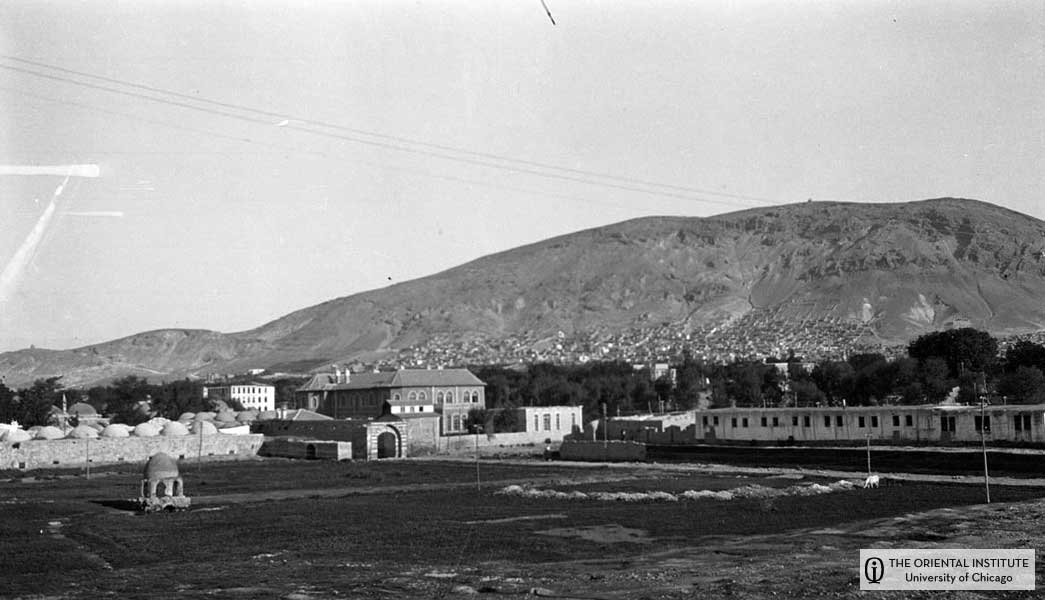

Damascus: A view showing the residence of King Faisal at the right. (N. 4016, P. 7576)

Damascus: A view showing the residence of King Faisal at the right. (N. 4016, P. 7576)

I have just come back from a very interesting interview with King Feisal at his house here in Damascus. He has a palace also, but prefers the informality and simplicity of his own house. I had sent up my letter of introduction from Lord Allenby by Consul Young, and the king sent word that he would see me at five this afternoon. As my responsibilities and anxieties for the success of the expedition have now really begun to relax, I told the boys we would go to a movie last night. They sold us the tickets without saying when the show began, but then told us it would be 9:30. We were then kept waiting until 10 before there was anything to see, but the amusing oriental life which crowded into the place.

It is now Ramadhan, and the people all fast during the entire day of course. Yesterday I enjoyed a walk with Nelson just at sun-down, as we looked into the cafés and restaurants and saw the people eagerly awaiting the boom of the sunset gun, which would permit them to fall upon the plentiful dishes which they had spread out in readiness for the onslaught. We bought some Ramadhan cakes, made of flour and nuts, and coated with sesame seeds,—really delicious things and made only during this month of fasting. Damascus is the greatest place in the Orient for pastries and confectionery, and they are as tasty as they look. The chief confection, besides many kinds of cakes, is khlawa or khlawi, which is made of sesame seeds, nuts and honey. It looks exactly like putty, but is delicious stuff and much used for food, as it is very nutritious. Mrs. Nelson put up a tin of it for us on this trip and we shall use it for lunches in the train. After the walk we took home our Ramadhan cakes to give some to the boys. This mention of Ramadhan really belongs to the above account of the visit to the movies, for in Ramadhan, the people sit up much of the night in order to eat. So they visit the cafés and places of amusement and stay there amusing themselves and feeding until toward morning. Even the children sat waiting until ten P.M. to see the movie show. If they venture to sleep very much, they have an arrangement with a drummer, who goes about the city all night beating his drum and waking the sleeping families for another feed before dawn. I haven’t yet heard the drum in Damascus, but that is what we found in Tripoli.

I finally went out to protest to the manager, that he was keeping us non-Moslems up too late for his bally show, and then told him I would take my party to more comfortable seats in the magnificent boxes(!), if we had to wait any longer. So he agreed and as we marched to our new seats, I was crowded against a bench by incoming people, and a huge projecting nail tore a great triangular hole in the leg of my trousers, my only traveling suit here,—one of those Jack Cooper made. I was disgusted, for Damascus is over 2200 feet above the sea, on the edge of the desert, and it is uncomfortably cool without woolen clothing. It was the suit I was expecting to wear at the audience with the king. Next morning I asked Consul Young, who lives at this hotel to help me out, and he sent one of his men to a good place to have the trousers repaired. When I went to his room this afternoon to go with him to the king, the trousers came back, so well mended that you can hardly find the place where they were torn. I had been wearing the alpaca suit you urged me to get (and very useful it has been), so I changed quickly to the heavier suit again as I was uncomfortably cool.

We had got into our carriage and driven a few yards, when we noticed a government automobile with a military driver just stopping in front of the hotel. One of the cavasses ran after us and told us it was an auto sent by the king, so we turned back, letting the carriage go, and entered the auto, which drove with a terrible noise of exhaust and whistle alarm through the narrow streets of Damascus, to the king’s house. We were taken by courteous young aides through a reception room to a rear balcony, overlooking a luxuriant garden, with orange trees and many others unfamiliar to me, among them a medlar pear richly laden with fruit overhanging a brightly playing fountain. Below us spread the houses and minarets of Damascus. As we chatted with a young pacha, the king stepped quietly out on the balcony, and greeting us with bow and hand-shake, much as any European gentleman would do, sat down and began talking with us in French, which he speaks even more haltingly than I. The conversation was quite commonplace until I brought up the situation of the Arab state and told the king of our journey from Baghdad. He was much interested, as the consul assured him we were the first non-Moslems (you can’t of course say “white men” to the Arabs!) to cross the desert from Baghdad to the Mediterranean since the Arab State began. Feisal asked me particularly about conditions in Mesopotamia, and we were soon on delicate ground when the question arose regarding Mesopotamia, or Iraq as the Arabs call it, and the feeling of the people about their rulers. I had to be careful about what I said about the feeling in Iraq toward the British, but I did not hesitate to tell King Feisal the facts regarding the feeling there concerning his own brother Abdullah, who claims the kingship over Iraq, as Feisal has gained that over Syria. I had to tell the King straight out that the hero of Iraq was not his brother, but the great Sheikh Ibn Sa’ud, a superb Arab, who some years ago led his people across the desert and captured Mecca. He is a Wahhabi, one of the sect of Puritan Moslems, who do not revere the saints, will not tolerate the sacredness of tombs, not even that of Mohammed at Medina, or of revered objects like the Kaaba, the sacred Black Stone at Mecca. They do not even allow smoking, so universal among Moslems. King Feisal did not take offence at my frankness, and when the audience closed, he asked me how long I was to stay in Damascus. Learning that I was to be here two more days, he asked the Consul to invite me to dinner for next Monday night, that is the day after tomorrow. He motioned me to pass out before him, which of course I could not do, and leading us across the reception room he opened the exit door with his own hands, as any courteous host of the humblest rank might do. We found the automobile waiting to drive us back to the hotel.

The delay here is very unfortunate. It will give me the interesting opportunity of dining with the king, but I had hoped to be in Jerusalem by Monday. The traffic is so light on the railway, that they run a train only three times a week. We shall reach Haifa Monday Night, June 1, instead of Jerusalem. It will take a day to go out to the Battle Field of Megiddo. The sunset gun has just boomed, and muezzin cries float over the city from all directions as I write, and I shall not reach Jerusalem now until the evening of the third. If I stay five days, as I expected, it will be June 9 before I reach Cairo, and I shall have only five days in Cairo, — far too short a time for all I have to do. Luckenbill goes back from Haifa to Beyrut with Nelson, and will stay there for a fortnight to develop our negatives, and pack our antiquities. He will come on with Nelson and his wife, leaving Athens by a Greek line about July 15.

This morning we wandered about in the bazaars, visiting the tomb of Saladin, and looking at the work of the coppersmiths, who are making very pleasing cylindrical vases, damascened with copper and silver, out of brass shells from the German guns here during the Turkish campaigns. While I was at the audience, the others have been walking out the “street called Straight”, and along the mediaeval wall many centuries later than Paul’s time, but containing a window identified with certainty as the one out of which he escaped from the city, let down in a basket.

Damascus: Straight street; the long bazaar showing the position of booths. (N. 4007, P. 7567)

Damascus: Straight street; the long bazaar showing the position of booths. (N. 4007, P. 7567)

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577