On train, between Haifa and Jerusalem, Palestine

June 3, 1920

I am sorry this letter has been so long held up, but until reaching Haifa it has been of no use to mail any letters. I will try to bring this down to date and mail it this afternoon at Jerusalem. Of course the dinner with King Feisal was very interesting. The Consul had not been using his dress clothes for so long that he was late in getting dressed. A pleasant young adjutant called before he was ready, saying the car was below waiting for us. I think we were a little late at a king’s dinner! Which was unfortunate in Ramadhan, when the poor King, like all his subjects, has been fasting all day!

This time we drove to the palace, where we passed through an endless array of sentries, aides-de-camp, adjutants, chamberlains, the last of whom filled three anterooms in succession. Stopping at last, we were introduced to the King’s younger brother, Zaid Pacha, who was regent in the King’s absence in Paris, and to Nuri Pacha, his chief general, who seemed little more than a boy. The King at once came out of his apartment and greeted us with noticeable weariness, though very courteously. He explained that on account of Ramadhan it was necessary to have dinner early, so we went in at once. The King motioned me to the seat on his right, which I was reluctant to take, as Uncle Sam was officially present, but of course I could not demur at any arrangement he chose to make. So the Consul and I sat facing each other on the King’s right and left. Next me on my right was the King’s brother, Zaid Pacha, and on his right Nuri Pacha. Opposite these two and myself, were the consul and a chamberlain, while at the end of the table facing the King was an officer whom I do not recall as to name and position.

The dinner was simple and about such as you would find in a fair hotel; — ending with the famous Damascus pastry and really luscious Damascus fruit. Politics had been rather delicate ground the day before, for I should have mentioned that the King said bluntly his present unhappy position between French and English aggression, the one in Syria, the other in Palestine, was our (America’s) fault! The Consul and I had both demurred, but I do not think it made much difference in the King’s feeling. So I avoided politics at dinner, and we talked of other things, especially of a possible visit by the King to America. After dinner the King led the way to a balcony overlooking the palace gardens and the entire city. There was a full moon, and below us lay the gardens of Damascus, the minarets and the sea of houses bathed in bright moonlight! It was a spectacle never to be forgotten. At my side too, stood the founder of a perhaps illustrious dynasty, beginning a new epoch in the age-long history of the Orient.

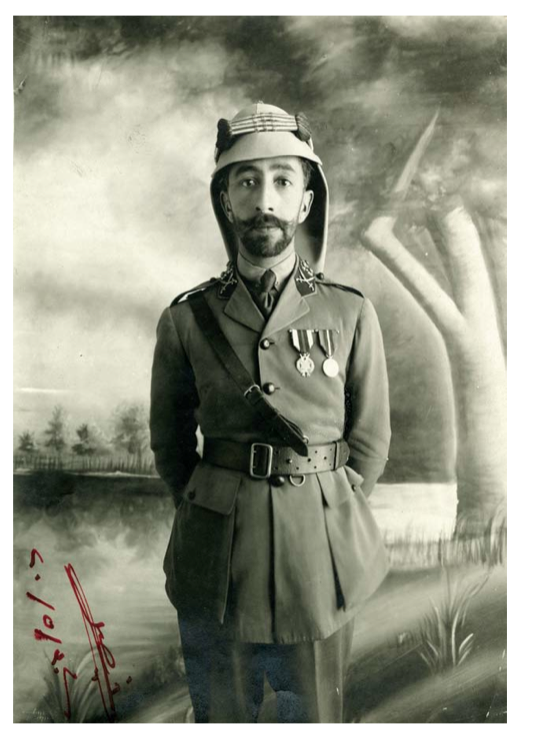

It was evident that the King was worn and weary with the fast, and the disturbed nights which it involves, so we took an early departure. Before doing so I took from my pocket a photograph of the King, which I had secured for the purpose and asked him if he would be kind enough to sign it. He took it at once to his desk and put on his name in red ink. Then the Consul and I bade him good-night, and I added that I hoped it was merely au revoir until his arrival in America. We drove through the moonlit streets of Damascus, with the gorgeously appareled cavass of the Consulate beside the driver, and it all seemed like a dream in fairy land.

A stock photo of Faysal that Breasted asked him to sign (OIM photograph P. 8247)

A stock photo of Faysal that Breasted asked him to sign (OIM photograph P. 8247)

The day had been a very busy one. We met a former student of the college who knew Nelson, and whom, to Nelson’s surprise, we found to be a member of the legislature of the new Arab (Syrian) state. Nelson said, “We flunked this chap several times at the college, and at last refused to graduate him. He went to America, matriculated at Columbia, and graduated easily!” He made a good impression on us, and said he would call and take us to a meeting of the legislature, which was one of the things I especially wanted to do. On our last day therefore, he called and we went with him to the meeting of the legislature. It is made up chiefly of members formerly elected to the Turkish Congress at Constantinople. We were introduced to the President of the chamber, Riza, a stately turbaned Syrian, who had long been exiled by the Turks in Egypt. Another former student of the college also came over to see us and we had a very instructive conversation on the political situation. The Syrians say we must intervene. I explained the difficulties. Taufik Mufarraj, the Columbia graduate, then asked me what we went into the war for, “Was it not to protect the small nations?” I said, “We went into the war to beat the Germans”. “Well, if that is all”, said Taufik, “then you have simply produced a situation which enables other nations to do just what Germany would have done if the Germans had won.” Now, that is not an easy statement to refute, in view of the experience of Syria.

These young men brought me a copy of the Declaration of Independence which they had passed on the 7th and 8th of March in the hall where we stood, and likewise copies of the Constitution which they were discussing and endeavoring to hammer into shape. The question of the morning and for seven or eight days preceding, was that of decentralization, — states’ rights; and the discussion was quiet, orderly and interesting. The old sheikhs in turbans were for enforcing complete centralization with no local independence at all; while the younger men in European clothes and wearing red tarbushes, plead for local autonomy and large local liberty. Before we came away they gave me a copy of a new souvenir of their independence, a book with a picture of the King and portraits of all the leading men who had put through the Declaration of Independence.

In the afternoon the President of the Chamber (the Legislature), with the two members, the former students of the college, called to see us at the hotel, and we had a very interesting conversation, which I wish I could have recorded in full, but I cannot find time even to keep up this scanty record. These matters pretty well filled up the day, and in the evening, as I have already recorded, came the dinner with the King.

The next morning early we were at the station to take the train for Haifa. One of the young railway officials was a former student of the college. His name was Fuad. He had reserved for us two three-seat coupes in first class; and had seen that they were locked. Then we enjoyed an example of the difficulties confronting the new Arab State. One of our coupes had been opened and appropriated by officers of the Army, and the other was occupied by a group of picturesque Bedwin, in full desert regalia. They were relatives of Sheikh Nuri Shaalan, whom you will find mentioned in Lawrence’s report (sent you in MS), as having borne a distinguished part in Lawrence’s campaign which destroyed the Fourth Turkish Army along the very line of railway we were going to traverse. One of them was a black Sudanese, and they said they did not see why Beduin should vacate for mere Turks, seeming to regard wearers of European clothing as Turks! One of them said he would plant a dagger in Fuad’s bosam if he attempted to enter the coupe, but Fuad went up just the same and climbed into the coupe. He summoned all the officials available but they could not free the coupes for us, for the Beduins had a note from the King! If there had been time other folks might also have procured a note from the King; — but as it was, we had to retire ignominiously to the third class where harim coupe was emptied for us. Then the train was held while the station master went back and brought us a cash refund of over 8 pounds, which they were at first reluctant to disgorge. Everybody is in terror of the Beduin, and their services in the war make them a strong group over against the townspeople and the educated modern class. The Beduin terrorize the towns much as did the cowboys of a generation ago on our own frontier in the western states.

We had a long weary ride on the cramped hard wooden benches of the third class, with many … natives trying to climb in with us at every station, but our much humiliated friend Fuad stayed on the train with us and kept them out. Imagine the situation however! The paymaster was traveling in our train and holding it up a half an hour at each station to pay two or three station employees their wages, and then to have a pleasant conversation with them afterward! The road led directly southward from Damascus, and had been built by the Turks as part of their Mecca line which they call the Hejaz Railway. It has a junction at Der’a with the line leading to the Mediterranean coast, to Haifa nesting under the seaward end of Carmel. We should have reached Der’a about noon, but the paymaster’s pleasant programme delayed us until 4 P.M. before we pulled in at Der’a. We managed to get some lunch there, and shifted into the First Class coupe, vacated by the relatives of Sheikh Nuri Shaalan. They had without doubt shared in Lawrence’s campaign and I would have been glad to talk with them, but they shouldered their sacks and marched off toward the desert.

Yarmuk River: A gorge with waterfall in the center. (N. 4023, P. 7583)

Yarmuk River: A gorge with waterfall in the center. (N. 4023, P. 7583)

Yarmuk River: A gorge showing windings of railroad track to avoid the steep grades. (N. 4027, P. 7587)

Yarmuk River: A gorge showing windings of railroad track to avoid the steep grades. (N. 4027, P. 7587)

Yarmuk River: A gorge showing erosion by rains on the bare sides of the ravines. Taken from track. (N. 4028, P. 7588)

Yarmuk River: A gorge showing erosion by rains on the bare sides of the ravines. Taken from track. (N. 4028, P. 7588)

Yarmuk River: Bedouins at work in the fields along the stream. (N. 4031, P. 7591)

Yarmuk River: Bedouins at work in the fields along the stream. (N. 4031, P. 7591)

Leaving Der’a we swung westward, leaving the Hejaz line which continues southward to Mecca. For two hours after this we rode westward down the beautiful gorge of the Yarmuk River, which flows into Jordan just south of the Lake of Tiberias (Sea of Galilee, or Lake of Gennesaret). As we reached Samakh, at the south end of Lake Tiberias, we had dropped nearly 3000 feet from Damascus, over 2260 feet above the sea to Lake Tiberias, 680 feet below sea level. At sun down we looked northward over the waters of “blue Galilee”, and after running for less than twenty miles up the valley plain of the Jordan, we turned westward again to cross the plain of Megiddo (or Jezreel or Esdraelon) to Haifa on the Mediterranean. We had had graphic evidence of a different kind of rule as we approached Samakh. Hanging from a telegraph pole beside railway line, we saw swaying in the wind the body of one of the Beduin who had been cutting the Haifa-Damascus line! He had shot two Jews, and resisting arrest, he had been properly quieted by the Indians sent to bring him in. But the Arab state cannot treat the Beduin in this way, — with results as above set forth. Other reminders of the disturbed conditions in these ancient lands were not wanting. West of Der’a at Muzerib I saw the wreckage of an airplane, quite likely to be the one you will find mentioned by Lawrence in his report, as wrecked by the enemy at this place.

We were glad indeed to pile out of the train at Haifa after ten o’clock at night. There were no carriages at the station, but we hired four porters to load up with the hand baggage and lest room should be in demand at the hotel, I asked Harold to run on ahead to engage beds while we came on with the porters and the luggage. It was very late by the time we turned in for it was a long walk from the station to the hotel. Nevertheless we were out at 5:30 the next (yesterday) morning, and were able to find two automobiles to take us down along the northern edge of the Carmel ridge to Megiddo.

Esdraelon: A view looking south toward Megiddo from near the railroad. (N. 4037, P. 7597)

Esdraelon: A view looking south toward Megiddo from near the railroad. (N. 4037, P. 7597)

It is the fortress commanding the middle pass across the Carmel ridge, the first transverse barrier met by an army advancing from Egypt into Asia. The first battle ever fought there of which we have any knowledge, was that of Thutmose III in the early fifteenth century B.C. I had Nelson write his doctor’s dissertation on this battle and the topography of the field where it was fought. He has taken a lot of photos on the spot and made an excellent study which is a real contribution; but we were anxious for some further photographs, and some of Nelson’s have faded and must be replaced by new ones, as the negatives have deteriorated. Since this earliest known battle on the spot, it has been the great battlefield between East and West for 3300 years, down to Allenby’s victory over the Turks on the same ground. The New Testament name of the place is Armageddon — simply “Mount (har or ar) of Megiddo”, and you may remember Allenby told me he had refused to be ennobled as Lord Allenby of Armageddon, but chose the less sensational form “Allenby of Megiddo”. There is a strong ancient Canaanite fortress on the site, — the very old city which Thutmose III captured by siege. It has been partially excavated, and you can see there was every reason why we wanted to reach it. Before we started we stopped at the local steamship offices and secured tickets back to Beyrut for Harold and Luckenbill, and we then drove merrily out of Haifa, skirting the north side of Carmel, where Elijah called down fire from heaven on his altar and discomfited the priests of Baal!!!!! About two miles out the driver of the boys’ car, a perfectly new Ford, while trying to examine his tires, drove the car into the ditch. We all went back and succeeded in getting it out. After having driven for hours along the hills on the north side of the plain of Megiddo, until we were far up toward Nazareth, which looks down on the plain from a lofty side of wonderful beauty on the north of the plain, we found that neither of our drivers knew the road. Across the plain southward, but miles away we could see the splendid site of Megiddo, dominating the whole plain, and commanding the pass across the Carmel ridge. The ruins of the old city or fortress rose quite clearly into view against the background of the Carmel Ridge.

The villagers told us there was a road across the plain toward it, so the best we could do was to take it, and go no further up to Nazareth. Having followed this road to the line of the Haifa Railway we found it went no further. We were now in the heart of the plain with no road evident for getting out. The stationmaster on the line told us we could follow the line eastward to the Afule road, which ran across the plain to Nazareth and southward to Megiddo. For over two hours we drove over plowed fields and dry stubble land, mostly on first speed at great expense of nervous strength and patience. The drivers had long since collapsed into hopeless imbecility. We finally came out on a spring where we replenished the almost empty radiators, and replaced a broken down tire case. Then as we drove away, our hero of the Haifa ditch, drove his car into green scum-covered pool which only a blind man could have failed to see. We got him out with much trouble, and made off for Afule about 3 miles away, and waited at the station, but the boys’ car failed to appear.

It was then one P.M. The station master said there was a train at two, — a goods train which would not carry passengers. I said it would carry six the next to Haifa, and sent our driver back to bring in the boys. His gears had been grinding badly ever since we started, and as he endeavored to start, he could not throw the outfit into gear. I then started him off on foot with a hasty note to the boys to come in on foot and catch the train back to Haifa. At the same time I found a squad of Indians, and asked for their sergeant, who acceded to my request to send a rider down the road after the boys, so that they might not miss the train. Just then a young British lieutenant blew in riding a dusty Ford, on his way to Ludd south of Carmel. I could not induce him to go down the road and get the boys in early enough for the train, as he had a long run to make before sunset. We sat down on the station platform, Luckenbill, Harold and I and ate some khlawa, the only food we had with us, as the lunch was in the other car! Just then the boys’ car hove in sight. The driver had run them into a mud-hole which we had been careful to get out and take our driver around!

A long tussle with station people followed. There was no passenger train for Haifa until the next afternoon. Just then our driver came along and said his car was running again. We determined to make a last effort to reach Megiddo along the Afule road, and off we went, — our car making a blood-curdling crunching at every revolution. A native boy from a threshing floor assured us there was a road, and also a bridge over the Brook Kishon, which you will recall from your Sunday school days. About a mile out, the boys’ driver ran into an enormous tangle of cast-off military telephone wire, which got mixed up with pretty much the whole car. It isn’t entirely good for the varnish on a new Ford. The next thing we knew, after we had finally extricated the much-wired car, we ran plum against a huge marsh with a channel of water in front of it, and no way around. We asked our young guide from the threshing floor, who had been riding on the running board, where the bridge was, and he gave it up.

I told the drivers to crank up at once and make with all speed back to the station, to try to catch the train. Both of them thereupon began staring helplessly at the walls of distant Megiddo which challenged us from across the plain. It was now not more than two miles away, — possibly three; but if we missed that train, we had before us a night in a native village, with no shelter, no food, and no bed or bedding. I found means to get the drivers going again, and off we raced for the station. I looked back just in time to see the boys climbing out of their machine. Their driver had raced plum into the mess of wire again, though we had just passed it by a wide berth. I made up my mind that they might spend the night there as far as I was concerned. You can understand what I mean by traveling with a kindergarten. Nevertheless, I almost died laughing. The train was already in as we raced for the station; but we caught it, and the boys finally pulled in, in time to climb in also.

I found an albino European or Oriental inspector, who said he could not let us go without permission from Haifa, and that he would telephone at once to Colonel Holmes, the British officer in charge there. He called up Holmes from the office just at my elbow as I stood on the platform, and I kept waiting to be asked to the phone, as I had told the inspector I wanted to speak to Colonel Holmes myself. Then this interesting Albino disappeared, and I learned afterward that he had been upstairs speaking with Colonel Holmes from there. He of course queered us. The native station master was helpless, as he had no permission to let us go on board. I tried to bluff him by getting into a box car with all the men, but he promptly sent for the military police who were not far away. We had to climb down and we saw the train pull out without us. I tried to get into communication with Colonel Holmes myself, but failed, as he had gone out.

There was only one last resort. That was to try to get to Nazareth. We started off on the Nazareth road, but after a few miles, just at the foot of the hills on the north of the plain our car gave one last crunch and quit. Shelton said he didn’t mind staying in the region, if obliged to do so. Bull, Edgerton and I were the only ones who were pushed by a fixed date for sailing from Alexandria; so I asked Shelton to go with Nelson and Luckenbill on foot to Nazareth, while we would drive there in the new car and try to scare up transportation for them to Haifa. By five P.M. we had reached Nazareth, found an old German woman running a little hotel. She told me the only automobile in the region was away on a trip; but I succeeded in engaging a carriage. As we drove out of the village, our three stranded companions came down the road and I told them of the arrangements. They had found a direct path, while we had zigzagged up the lofty hills very slowly and they had come up about as fast as we did. I sat beside the driver and saved the car twice on steep and winding zigzag roads from going over the edge. After two hours of grilling experience like this we drove up to our hotel at 7:15 P.M. The boys got in at ten, and found a good dinner awaiting them. Meantime a gentleman in a red tarbush showed up and told me he was the owner of the cars, and that he wished his money, 20 pounds, for the use of them. I informed this gentleman that I had never passed a word with him before in my life, and consequently had never agreed to pay him anything. The bargain had been made with the driver of our car, who had limped into Nazareth with the wreck just as we drove out. We gave each driver two pounds to pay for gasoline, and that was the last we heard of them. Such was one day’s work, making a further survey of the Battle Field of Megiddo!

I turned in at nine, but was out again this morning at 4 to catch the six o’clock train for Jerusalem. I am nearing the end of this record, for as I write we are passing up into the hills of Judaea from the sea-plain. I have been anxious to see the old city of Gezer, quite near the line, and visible after leaving Ramleh. It once controlled the valley road from the sea-plain up through the hills to Jerusalem, and has been excavated by the English. The Pharaoh once presented it to Solomon as dowry for the Egyptian king’s daughter. Shelton was on the watch for it, — our redoubtable Shelton! I might have known he would miss it, but I wanted to finish this before reaching Jerusalem, so as to be able to mail it at once; so I kept on with my writing. I have just looked to inquire of Shelton about Gezer, and he replies that he isn’t sure whether something he saw on a hill where Gezer ought to be, was the place or not, but he etc. etc., etc!!!!! Anyhow we have passed it! I confess, I am chiefly interested now in getting home. We have accomplished all that we set out to do, except a more full and satisfactory examination of Syria. For this exception the French occupation is responsible. As far as museum acquisitions are concerned, I have every reason to feel contented. We shall be able to make a creditable showing, and one that will not fail to bring in more funds for Oriental work.

I enclose two cards from Nazareth for the children. I have a little earthen ware jar, for each of them, with the name Nazareth moulded into it. They can show these in Sunday school, and the little folks will be interested in things that were made in Nazareth.

I shall follow this soon, and there will be little time now to write. I shall soon be able to talk, and that will be better! Love to the big boy, and the babies and their dear mother! Always affectionately, James.

Hotel Allenby, Jerusalem, Palestine, Thursday Evening, June 3, 1920.

I have been trying ever since I reached civilization at Aleppo, to find out from Cairo whether the consul had my cablegrams from President Judson, but have failed at every point to elicit a reply from the consul. I tried again yesterday at Haifa, and when we drove off in the morning, I left with the landlord typewritten copies of the telegrams I charged him to send at all costs. When I returned in the evening, he handed them back to me with the report that the telegraph clerk required them to be written on the form, — a thing no clerk has ever exacted before in all my oriental experience. So I came on to Jerusalem, and the first thing I did here was to make for the telegraph office. Arrived there I found it closed. It was King George’s birthday, and all the telegraph offices in Palestine were closed! Likewise the post offices! So I could not mail this today as I had hoped. I find out also that the trains for Cairo run only three times a week, and we shall have to stay here until next Tuesday the 8th, just a week before I sail from Alexandria. This means a desperately hurried time in Egypt. I am still in the dark as to the amount of my credit in Cairo, and whether I can pay my debts there; but as the president’s Baghdad cablegram gave me an immediate credit for Asia of $25,000, I take it he must have expected to cover the Egyptian indebtedness or he would not have authorized further outlay in Asia. But meantime I am vexatiously in the dark. I shall cable to the president tomorrow, asking that Cairo cablegram be repeated to me there, and hope to get a reply before I leave; but the cables are so slow that it is difficult to get a reply back from America in less than a week.

I called on Clay this afternoon and found he was at a fete in honor of the King’s Birthday. I went over to the fete and found him and Garstang, Dr. Peters and others. Lots of local gossip and political news! To my amazement Clay tells me that the British School of Archaeology here has only 500 pounds a year and cannot get any more. I walked over with him to the building site of the American School which makes an impression very favorable and not at all in accord with the unfavorable reports of its suitability I have heard elsewhere. It is directly alongside the beautiful institution of the French Dominicans, just outside the Damascus gate on the north of the city. Clay and I went in and called on the head of the establishment, the able and charming Pere Lagrange,—also Pere Dhorme, their Assyriologist, and Pere Vincent, the best of the Palestinian archaeologists, but the last was not in. As we were finishing dinner tonight, Clay and his wife called, and we had a further little visit.

Clay tells me that the British authorities have clamped on the censorship lid here, and all letters are now censored. I am greatly concerned lest they have scooped in the whole of my journal of the Baghdad-Aleppo overland trip, which I could not reproduce, and which I sent you by registered post from Aleppo. I fear it must have come through the censorship here. You will know before you read this, whether it has been lost or not. It was mailed on Tuesday, May 18th from Beyrut. In any case I shall not post this present section until I reach Egypt next Wednesday. Meantime I will send you a picture card, and I am sure my cable will keep you from worrying at the failure to receive letters. It will be a crying pity if my journal of this unique Baghdad-Aleppo trip is lost. Everybody here is amazed that we got through. I have received no reply to my Tribune cable, and I expect that was captured by the censor also. Well, it can all be kept till I arrive. I find no telegram here from Beyrut confirming Naples reservation on the White Star Liner “CRETIC”, sailing from Naples June 25th., but I can cable to Naples again if I don’t hear soon.

I’ve included some of Shelton’s pictures from Jerusalem as well:

Jerusalem: Jaffa Gate. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8192)

Jerusalem: Jaffa Gate. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8192)

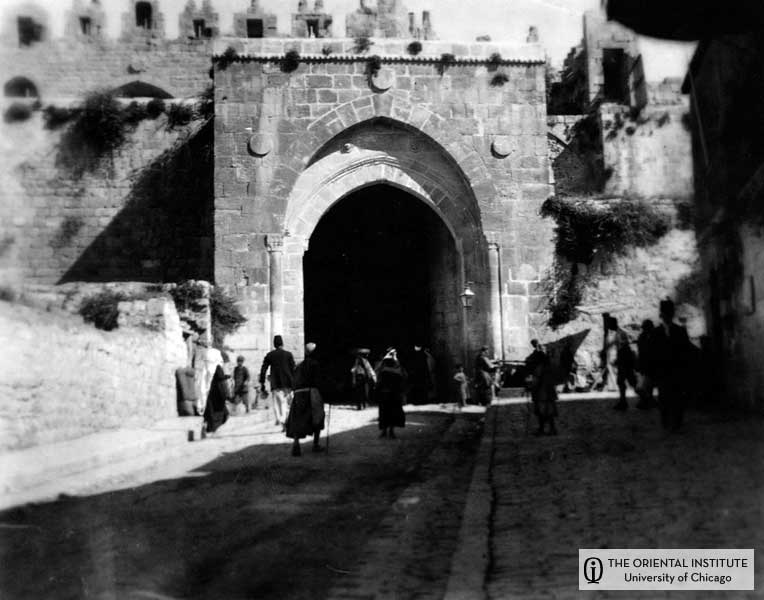

Jerusalem: View from the inside of the Damascus Gate. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8194)

Jerusalem: View from the inside of the Damascus Gate. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8194)

Jerusalem: View from the inside of the Damascus Gate. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8195)

Jerusalem: View from the inside of the Damascus Gate. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8195)

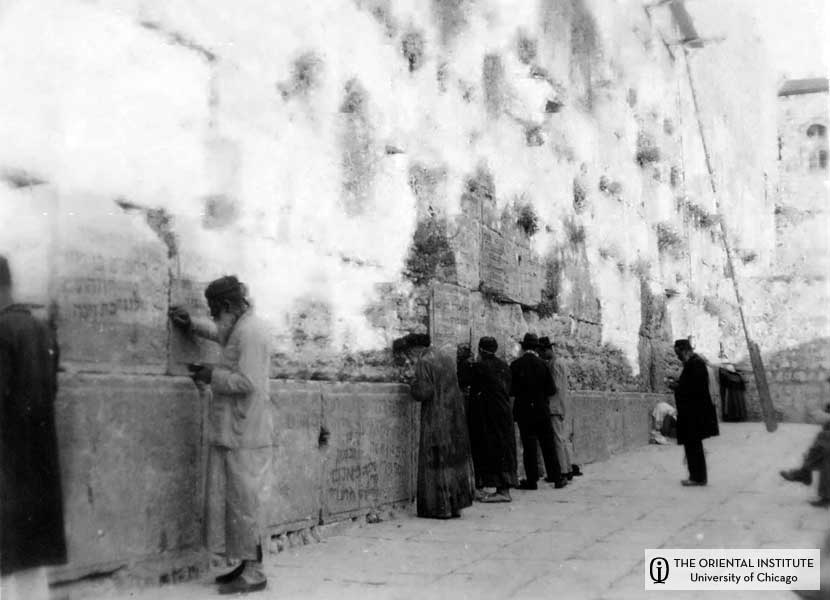

Jerusalem: The Wailing Wall. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8197)

Jerusalem: The Wailing Wall. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8197)

Jerusalem: Excavations on the north side of the temple area, showing the deep wall which followed the Tyropean Valley between the Temple and the Holy Sepulchre. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8198)

Jerusalem: Excavations on the north side of the temple area, showing the deep wall which followed the Tyropean Valley between the Temple and the Holy Sepulchre. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8198)

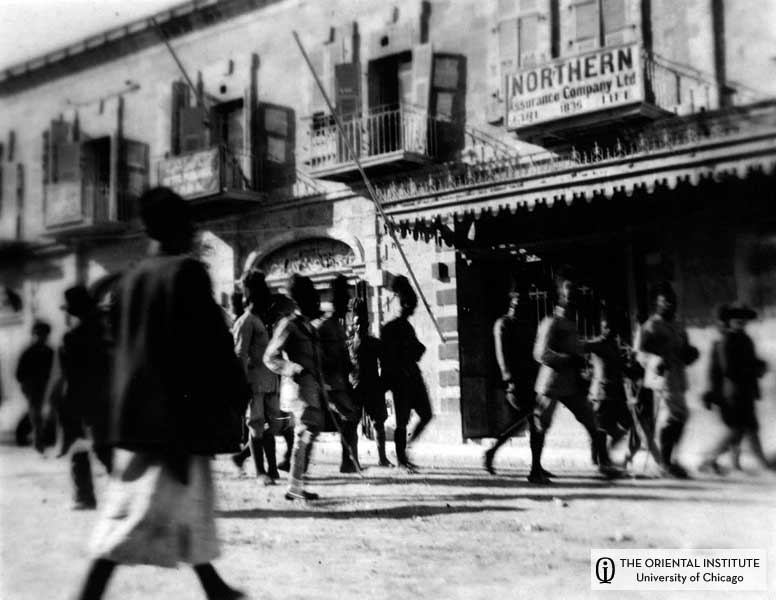

Jerusalem: Abyssinian soldiers on the streets of Jerusalem. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8199)

Jerusalem: Abyssinian soldiers on the streets of Jerusalem. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8199)

Jerusalem: A street. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8202)

Jerusalem: A street. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8202)

Jerusalem: A street. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8203)

Jerusalem: A street. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8203)

Jerusalem: The Garden of Gethsemane. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8204)

Jerusalem: The Garden of Gethsemane. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8204)

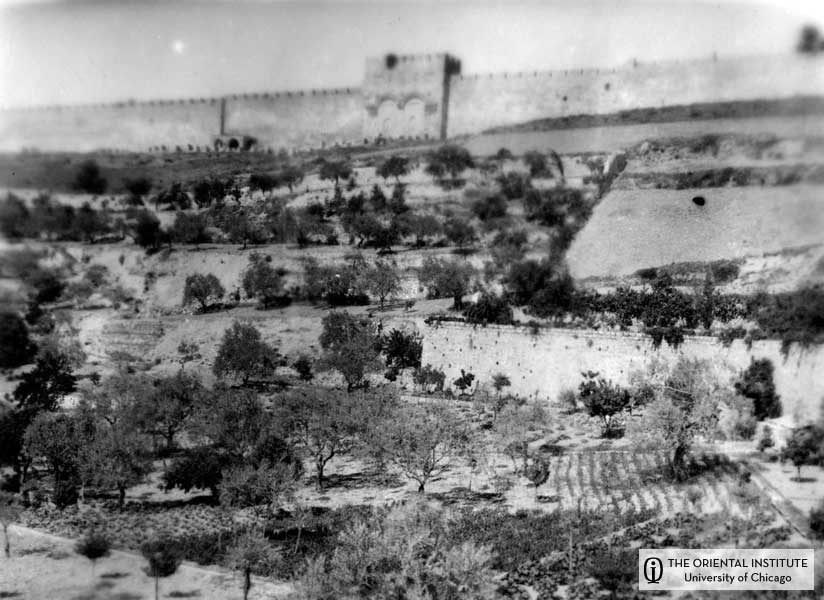

Jerusalem: East wall and the Golden Gate from Kidron. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8205)

Jerusalem: East wall and the Golden Gate from Kidron. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8205)

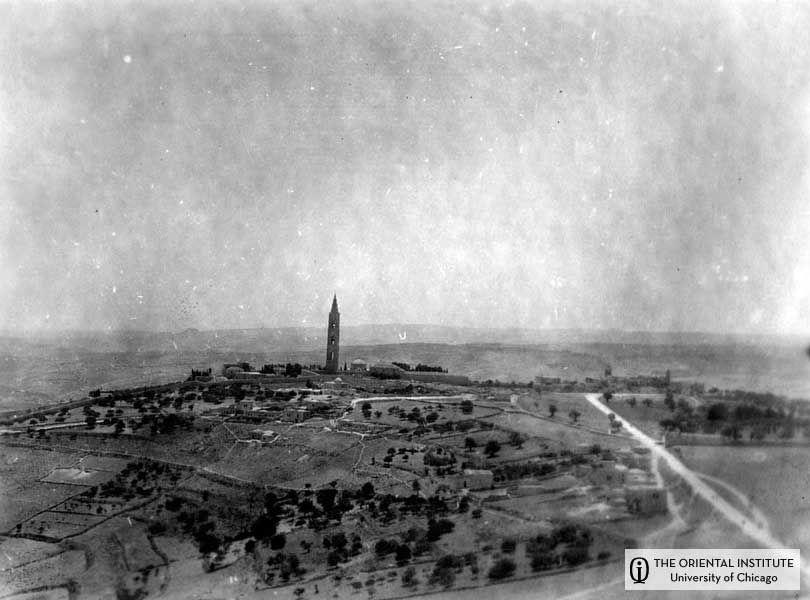

Jerusalem: View from the top of the tower of the German hospice on the Mount of Olives, looking over Jerusalem on the right, the Russian tower in the center, and the Dead Sea and Moab on the left. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8206)

Jerusalem: View from the top of the tower of the German hospice on the Mount of Olives, looking over Jerusalem on the right, the Russian tower in the center, and the Dead Sea and Moab on the left. Photo by W. A. Shelton. (P. 8206)

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577