My arrival in Egypt

November 30, 1919

To catch all my readers up on the happenings in Egypt so far, I’ll be paraphrasing, but also quoting extensively from letters written to my family and associates.

Here am I with the bright Egyptian sunshine all around me, and palms nodding in the Nile breezes and the strange crooning of the falcons soaring outside in sharp silhouettes against the luminous sky and a thousand memories and associations throng my mind as I see and hear and feel dear old Egypt all around me. I have such a lot to write you and seemingly so little time in which to do it, for a host of things have crowded in upon me at the very first. (To Frances; Sunday, November 2, 1919 - Cairo).

It is wonderful to be back in Egypt after so long, and yet so much has changed in the wake of the war, and the political turmoil has left a palpable tension in the air. There is unrest throughout Egypt:

But these troubles seem to be confined to these two big towns. The country people have had enough, and are quite ready to settle down under British authority; but the little tarbushed effendis in Cairo and Alexandria are still making trouble. Allenby, who was expecting to spend a long vacation in England, has already returned, and arrives this morning. There is trouble in the air, and the outbreak in Cairo is likely to come at any minute. You need not have the slightest anxiety. The trouble will be confined to certain quarters, just as was the negro rioting in Chicago. The authorities are quite ready and indeed are hoping that the lid may blow off very violently in order to show the agitators the strong hand at once and without mercy. The country is full of British troops and at Shepheard’s and here (the only two hotels that are open), one sees almost nothing but khaki on the terrace and in the dining room. (To Frances; Sunday, November 2, 1919 - Cairo)

I have spent almost all my time so far on various diplomatic errands, hobnobbing with the powerful men of the British Empire here in Egypt. The rest of my time is consumed sorting through all that the many antiquities dealers have to offer. For during the war they were unable to sell any of the artifacts, and now there is a huge backlog and more things to purchase than have ever been available before! Lord Allenby is finally back in the country, and there was quite a to-do about his arrival; no one could have missed it:

It was on my way back from seeing General Bols that I learned of Allenby’s imminent arrival. As I went down to the American Agency, the native police were everywhere, and the streets from the station right down to the gates of the British Residency were lined on both sides with British troops with fixed bayonets. As the train pulled in the entire air force, a beautiful squadron in V formation, swept over from Gizeh, circled over the station and followed the High Commissioner’s carriage from the station to the Residency. It was an imposing demonstration of British power in the East, and it must have given the hysterical nationalists here something of a jolt. (To Frances; Tuesday evening, November 11, 1919 - Cairo)

Last Thursday (November 27th) I had an extremely interesting meeting with Lord Allenby after a formal dinner at the Residency, where he opened up to me about his feelings on the British presence in the Middle East, and the troubles we are all facing at the close of the war. Naturally, I must request that you keep this to yourselves, but I recorded our conversation nearly verbatim in a letter to Frances, so I’ll retranscribe it for you here (I have noted my responses, introduced with my initials, to Lord Allenby when appropriate, but his words were what I considered the most important):

“My impression of [President Woodrow] Wilson differs from yours. To me he seemed a man of conviction, with a good deal of strength and courage. I heard him tell the peace Commissioners what he had done for, and what he expected to see done, and he insisted that it be done. I had to deal with him in the matter of Syria and its future, and I explained to him my attitude and my situation, which was an unusual one. I always maintained that I was commander of an international army. I always insisted that I was not taking any territory for England or as an English commander. I know there are legal difficulties. In handing over Syria to the French now, we are involved in a transaction of doubtful legality. Your Mr. Justice Brandeis, when he was over here, was not sure in his own mind what the legal status of the conquered areas might be, I said to him then that I was not of course a jurist or possessed of any knowledge of international law, but the situation now seemed to me like this:”

“I have conquered and occupied certain regions of the Ottoman Empire. I call it Occupied Enemy Territory (O.E.T.), and I have divided it up into administrative districts, and given the whole region an administration (O.E.T.A.). I propose to maintain that administration and keep the countries occupied in quiet and peace, until the peace treaty makes other disposition of the territory. Then I must leave legal complications to later settlement in so far as I can.”

“I am now withdrawing my troops from Syria because the Foreign Office has instructed me to do so, and my retiring forces are being replaced by French troops. This change is a difficult one and full of danger. I said so when I was asked to come to Paris to confer with the Peace Commissioners before the Peace Treaty was ready. President Wilson asked me what would happen if Syria were at once turned over to the French. I told him it would immediately result in a terrible war with the Arabs, which would draw in all the surrounding territory, and probably much more: the Young Turks, the C.U.P. (Committee of Union and Progress), the brigands of Talaat and Enver, the Kurds and Armenians, the Wahabis and not least the Bolsheviks. It would doubtless spread far into Asia and set the world on fire again.”

“Wilson said to me, ‘Will you make an address before the Peace Commissioners?’ I replied that I could not do that, but I would be glad to answer any questions put to me. The next day Wilson asked me the same question in the presence of the Peace Commissioners, and the French, including Clemenceau, heard me make the same answer. Wilson then asked me how the wishes of the peoples of the conquered areas of the Near Orient might be ascertained. I told him by asking the people openly and directly, and he then said a commission should be sent for this purpose.”

“Later, when I was called to Paris after the conclusion of the Peace Treaty, to talk with Clemenceau about the future disposition of Syria, I could talk to him very frankly, because I have known him for a long time, and we are good friends. So I said to him, ‘You know me well, and we have been good friends. You must believe me when I tell you there is absolutely no occasion for all this French sensitiveness about Syria. We don’t want it. We shall be glad enough to get well rid of the responsibility for it. There is not an Englishman, whose opinion is worth having, who feels otherwise. We are quite ready to hand it over to you, but we want to be sure when we do so, we can do it without stirring up further trouble out there. Certain actions of yours out there have given us grave anxiety. They must be stopped, and your policy changed. Your people out there have been deliberately trying to stir up trouble and excite pogroms, in order to give you a chance to step in and take possession of territory that you want, under pretense of restoring order. You know it is going on and it must be stopped. We are quite ready, as I said, to retire our troops as fast as you can move yours in, but when this transfer has taken place, we want peace in the whole region, so that Syria and the whole Near East may return to normal conditions and no longer be a danger to us and to the whole world.”

J.H.B.: “But Lord Allenby, the Syro-Palestinian frontier has been in just this condition for thousands of years. It will be nothing new if the French do not succeed in keeping it quiet.”

Allenby answered instantly, throwing out his hand and seizing my arm as he did so: “But my dear sir, while that is very true, it has never been true before that the whole world was ready to take fire from this Syrian blaze. And so I told Clemenceau. He replied, ‘Yes, I think you are right.’ Well, then, said I, if you think I am an honest man and I think you do, then believe what I have said, and shape your policy accordingly. Clemenceau responded, ‘It isn’t as simple as that! I do believe you are an honest man, but I do not believe that the British nation is honest and I do not trust them.’” “This then is the situation as I am withdrawing my troops from Syria. Fortunately the French have appointed an excellent man to assume control there - General Gouraud, a man four times wounded in the present War and now lacking an arm.” “I am leaving for Beirut tomorrow so that he and I can ride through the streets with our arms around each other, you know,” (Allenby’s eyes twinkled), “for public consumption. It will let them know they can’t hit Gouraud without hitting me. But a much more important reason for my going is to urge him to concede one thing to avoid trouble. That is, to leave my troops in the northern Buk’a. If my posts are removed and replaced by French troops, there will be an outbreak, and I fear a serious one.”

“The commander of all the Arabs openly said he would not submit to French control, and that if we supported French government over them, he would fight us too.”

J.H.B.” “French troubles up there will always be yours also.”

“Certainly! Of course I could not let such defiance pass. I sent a civil commissioner up to see the Arab leader, and he repeated his statement that he would not submit to the French, and he would fight us if we tried to make him. I think I was in the worst funk I have had in this war, for I expected a violent outbreak if I took action against him. But I sent troops at once to arrest him, take him to Haifa. I have been in an awful funk for the last twenty-four hours, expecting the trouble to come, but nothing has happened, and I am very glad I did it for the sake of the French. But I ran a great risk. Under Gouraud, however, I look for improvement, in spite of the unfortunate memories left by Picot.”

J.H.B.: “Picot was the man who fled from Beirut at the outbreak of the war and cruelly failed to destroy his confidential correspondence, leaving it to incriminate the best friends of France among the Syrian natives, so that many of them were shot or hanged, was he not?”

“Yes, that is the man. You can understand the resentment of the Arab leader whom I have just arrested.” (To Frances Breasted; Sunday Evening, November 30, 1919 - Cairo)

I had never thought to be privy to the power struggles behind international diplomacy, and to see the intense maneuvering deciding the fate of nations is absolutely fascinating. Though I now fear what I will find as the situation in the Arab state if the French rule is so controversial. But my readers should not fear, I have been forewarned, and shall be alert when I travel to that area.

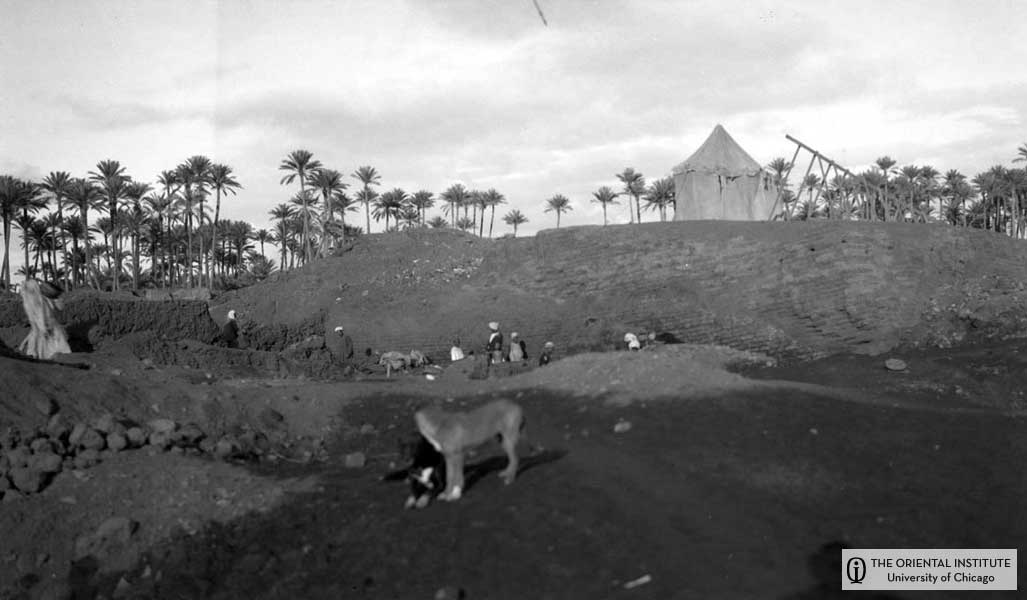

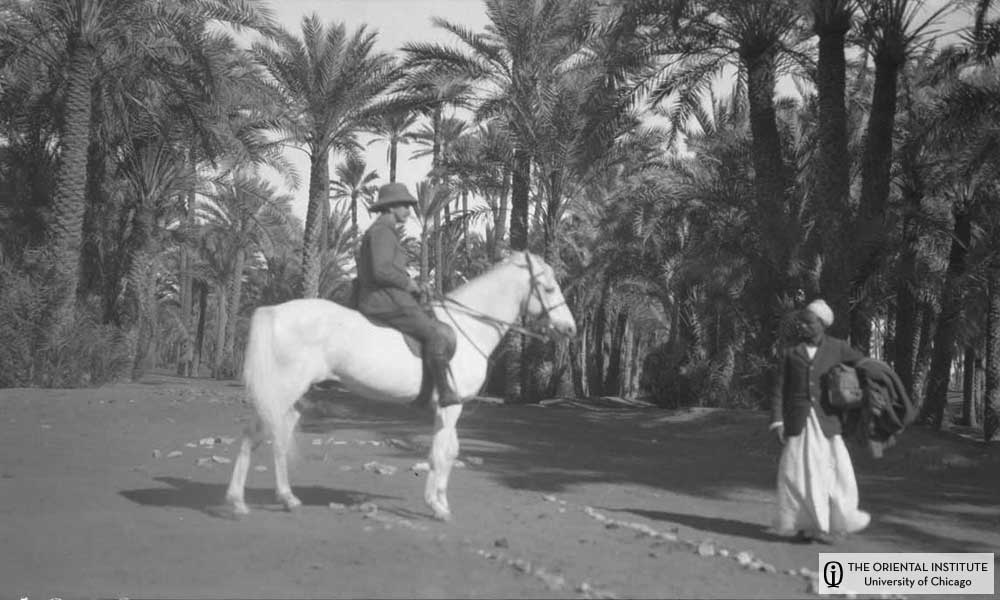

On a lighter note, I also had the opportunity to visit Clarence Fisher from the University of Pennsylvania at the palace of Merneptah, and I spent my Thanksgiving holiday with him. I’ve included some pictures here for my readers.

Memphis: View of the palace of Merneptah, showing excavations of University of Pennsylvania in progress near the interior southwest corner. (N. 4221; P. 7820)

Memphis: A view of house walls belonging to the late period as excavated by Mr. Fisher of the University of Pennsylvania. (N. 3367; P. 6927)

Memphis: A view of the excavations in progress by the University of Pennsylvania. (N. 3363; P. 6923)

Memphis: The Egyptian cur belonging to Mr. Fisher of the University of Pennsylvania. (N. 3364; P. 6924)

Memphis: View of alabaster sphinx, uninscribed, showing head and forepaws; excavated in 1912. (N. 4217; P. 7819)

Memphis: University of Pennsylvania excavations. (N. 4219; P. 25981)

Memphis: Excavations of the University of Pennsylvania. (N. 4218; P. 25980)

For the full story of my exciting trip come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours: Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm Sunday noon to 6:00 pm Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook to see even more pictures at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577