Northern Indian Ocean, two days from Bombay

February 27, 1920

Friday Evening,

I have really been so tired writing up my purchase lists, that I have loafed a little in the evening and hence the long gap in this important chronicle. Yesterday I finished the lists at last with a long sigh of relief, and this morning I wrote a statement or series of suggestions for the improvement of the Service des Antiquités of the Egyptian government for the Milner Commission. I have another day for getting off quite a series of belated letters before we reach Bombay day after tomorrow (Sunday). The six day voyage from Bombay to Bosra will, I hope, give me a little time to look through the collection of travelers’ reports which Luckenbill has brought out. Of course I should have been at work on this material long ago, but the lists have kept me tied down every minute. It is however, very gratifying to read over these lists now and realize that all the fine things they contain will make Haskell for the first time really an oriental museum worthy of the name.

Today we passed a sister ship of this line outward bound for New York and we wished we could toss a letter to her deck and send news directly home. Thus far the Indian Ocean has been smoother than the Red Sea, and we have had ideal weather, though it is very hot. It makes one wonder what it will be like coming back for without our electric fans life in the staterooms would be impossible. Ours got a kink in it today and wouldn’t go, and we nearly stifled until it was put in order again.

The Red Sea was to me intensely interesting. Some of the people on board who had been reading my books sent a committee to me asking for a lecture, and the result was I put on my dinner coat and gave them a talk on “the Red Sea in History”. Notices were also put up in the second cabin, and the people from there, including also some Jesuit friars, came over likewise and we had a dining room full. The captain let me select the necessary maps from his charts, and this was a great help. I used to look at the Bab el-Mandeb, at the south end of the Red Sea when I was a little fellow in tiny red brick school house at Downers Grove, and wonder and wonder how such far off lands and places looked and how it would seem to be there. Even to an old timer such as I have come to be, it is very far from a matter of course to pass through this famous strait. Here were the desolate rocky islands, so long infested by Arab pirates, and the scene of many an adventure of our old friend Sindebad. One of them, the island of Perim, is held by a British garrison, and is used as a large and important coaling station, although it is entirely without water, which has to be obtained by distilling sea water. The African side is the land of Punt, which the first Egyptian ships began to visit some 5000 years ago, and here lived the fair fat queen, who was visited by the fleet of Queen Hatshepsut which you have seen so beautifully sculptured and painted on the walls of the Dêr el-Bahri temple at Thebes.

We have on board a Dr. Chalmers, head of the government medical laboratories at Khartûm, who says he has often crossed from the Nile to Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast, and has employed a little government steamer for biological investigations of that coast. He thinks it would be quite possible to charter this boat for a reasonable sum and make an archaeological survey of the coast. As you know it is filled with inscriptions still uncollected which would reveal to us the history of the development by which the Far East was gradually drawn into connection with the Red Sea, — a process by which the models of Egyptian ships, and the whole physical equipment of Egyptian navigation passed into East Indian waters and even into the Pacific, where many of its highly individual characteristics may still be found in the Far Eastern shipping of the present day.

We have on board a Dr. Chalmers, head of the government medical laboratories at Khartûm, who says he has often crossed from the Nile to Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast, and has employed a little government steamer for biological investigations of that coast. He thinks it would be quite possible to charter this boat for a reasonable sum and make an archaeological survey of the coast. As you know it is filled with inscriptions still uncollected which would reveal to us the history of the development by which the Far East was gradually drawn into connection with the Red Sea, — a process by which the models of Egyptian ships, and the whole physical equipment of Egyptian navigation passed into East Indian waters and even into the Pacific, where many of its highly individual characteristics may still be found in the Far Eastern shipping of the present day.

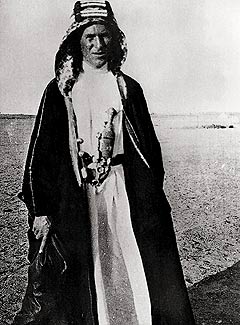

Leaving out the American commercial men, who spend most of their time in the smoking room playing cards for beer (one of the coarsest and most vulgar lot I ever came across), there are some interesting people on board. Colonel Saunders is a British officer who went through the Dardanelles and Palestine campaigns, and was in command of the whole north quarter of Cairo during the March insurrection of last year. He is going out to central Africa to raise tobacco, leaving the Mrs. at home, as it is evident he and she don’t get on. He is a very attractive fellow. A big and ponderous, florid-faced Briton is Major Barlow. He also sits at our table and though very taciturn and modest, we have at last induced him to talk. He was chief liaison officer between the famous Lawrence in Palestine and Allenby’s headquarters. Perhaps you have not noticed anything about the extraordinary Lawrence. He was a student of Hogarth, the classical archaeologist, director of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, whom I met there, and whose letter of introduction to Allenby I copied and sent to you. Lawrence went to the East with Hogarth and became familiar with the Arabs and their life. He gained an unusual acquaintance with Arabic dialects, and learned to know the most prominent Arab leaders.  They all liked him and he had a strange and unprecedented influence over them. When the war broke out and it was seen that the Arabs only needed proper leadership to rouse them against the Turks, the English sent Lawrence out to undertake the task. What follows reads like a romance. This young Englishman roused all Arabia, and marched with the Arab leaders at the head of thousands of desert tribesmen on Allenby’s eastern flanks as he advanced northward against the Turks. Lawrence left the bulk of his Arabs behind, after reaching the head of the Red Sea at Akaba, and advancing northward on the east of Jordan with only a thousand of his best men, he flanked the Fourth Turkish Army on the east of Jordan and cut all the four railway lines which connected the Turks with their northern base at Damascus. In terrible danger of being overwhelmed by a sudden onslaught of the Fourth Army, some 20,000 strong, Lawrence maneuvered so cleverly that he kept out of the way of harm, while constantly harassing the discomfited Turks until he had their whole Fourth Army on the run. He killed about 5000 of them, took about 8000 prisoners and scattered the rest completely. His triumphant entry into Damascus reads like a story from the crusades.

They all liked him and he had a strange and unprecedented influence over them. When the war broke out and it was seen that the Arabs only needed proper leadership to rouse them against the Turks, the English sent Lawrence out to undertake the task. What follows reads like a romance. This young Englishman roused all Arabia, and marched with the Arab leaders at the head of thousands of desert tribesmen on Allenby’s eastern flanks as he advanced northward against the Turks. Lawrence left the bulk of his Arabs behind, after reaching the head of the Red Sea at Akaba, and advancing northward on the east of Jordan with only a thousand of his best men, he flanked the Fourth Turkish Army on the east of Jordan and cut all the four railway lines which connected the Turks with their northern base at Damascus. In terrible danger of being overwhelmed by a sudden onslaught of the Fourth Army, some 20,000 strong, Lawrence maneuvered so cleverly that he kept out of the way of harm, while constantly harassing the discomfited Turks until he had their whole Fourth Army on the run. He killed about 5000 of them, took about 8000 prisoners and scattered the rest completely. His triumphant entry into Damascus reads like a story from the crusades.

I have just been reading his own MS report to Allenby, which Major Barlow had in his bag. The French are so insanely jealous of Lawrence’s power and influence among the Arabs, that the British have not published Lawrence’s report for fear of offending the French. It is a pity, for it is an extraordinary document. I am going to ask Barlow to let me make some notes from it. If you can secure at the University Library the last October number of the journal called ASIA, you will find in it an article by Lowell Thomas on Lawrence which will give you a readable account of his work among the Arabs. Lowell Thomas was giving a picture show in London when I was there, containing much of this article. He is a cub reporter from Chicago, — ignorant, unlettered and vain, — an altogether absurd little rooster. Mrs. Greg asked me in Cairo if I had heard him, and said that as an American she felt utterly humiliated at the performance in London. If you get the above number of ASIA you will find Mr. Thomas hobnobbing very familiarly with Lord Allenby, the Duke of Connaught, Lawrence and others. Major Barlow was looking over the article in ASIA last night and snorted with disgust. “Why,” said he, “I took the little cad from Cairo to Akaba myself, when I happened to be going up, for we would not let him go alone. He never got over eighty miles from Akaba, and we let him stay only ten days all told, from the day he arrived until he left; and here he is with Feisal watching the battle of Maan. He never got anywhere near Maan!” So much for enterprising young America in the Near East!

Lawrence has written a book of several hundred thousand words recounting his work in the Near East. He was carrying the MS in a bag on a train in England, and on leaving the train, he took the bag along, not discovering until after he had left the station that the bag he held in his hand was a duplicate bag, exactly like his own, with his initials and other marks on it, and the same marks of age. Someone has gone to great trouble to make an exact duplicate of his bag in every particular. The question arises who it was who would have had reason to suppress his book, and Major Barlow, who told me the story, answers the question without hesitation. The bitter feeling that I have found here between the English and the French has surprised me greatly. There is open talk of a future alliance between England and Germany whenever English public opinion will permit. They call France the bully of Europe, and they are sick and tired of kow-towing to the French. France on the defensive was magnificent, but France victorious is sadly disappointing.

Mr. and Mrs. Edwards of Hamadan, Persia are interesting people. He is a manufacturer of rugs at Hamadan. Mrs. Edwards is a member of the American Oriental Society, and I remembered her having read a paper at one of the meetings, after which we happened to sit opposite each other at the lunch. As Mrs. Warren is going to Persia she has found Mrs. Edwards very helpful, and they are much together. Mrs. Warren is working all day long at her type-writer, preparing a long report on YMCA work for the headquarters. Evidently she does a great deal of work for them. I learn from the table talk that she has made her great interest in life the two little boys of our former colleague in political economy, Davenport, now in Cornell, whose wife is her intimate friend. She is devoted to these two little chaps, and is saving all the money she makes writing, for them. This gives her an interest and a purpose in life. She knows an immense deal about the faculty history at the University of Chicago, and it has been rather interesting to hear whole chapters of the earlier biographies of my colleagues, about which I knew nothing. She plays deck tennis, a new game introduced by Ludlow, with the other members of the expedition on the forward deck for an hour after tea every day, while I am playing shuffle board with the young people at the stern. There has been a tournament in shuffle board, and my partner and I have won ten games out of eleven played, which has given us the lead on games.