Launch "Ballia", Shatt el-Hai

March 21, 1920

Launch “Ballia”, Shatt el-Hai above Suwêg ibn Sagbân, Mesopotamia, Sunday Morning, March 21, 1920

My dear, dear boy —

We are slogging along against the current, a strong one — making for Kal’at-Sikkâr — a run of four hours. An hour’s ride from the river on our right (east), is Tello as de Sarzec, the excavator called it, though the natives tell me it should be Tell-‘o and of course you see the importance of the difference.

How I wish you could join us on this trip. You couldn’t ask for a finer set of boys than I have with me, and you will be surprised to know that the keenest and most helpful of all is Edgerton. But none of the boys sees what to do in the constant exigencies or even crises so frequently recurring on a trip like this. For example, we have just had a fire on board and narrowly escaped seeing the launch burn up. We have eaten breakfast on board and our cook filled the oil stove while it was alight and set the whole outfit on fire. This would never have happened but for the poor devil’s attempt to protect the fire from the wind, for we are out in a driving wind storm. Had the boys been wide awake they would have made him a sheltered nook with a piece of tenting, as I tried to do and nobody lent a hand.

We are going up the Shatt el-Hai some 20 miles north of Shatra el-Muntafik. The water is so muddy I haven’t had a decent wash for 48 hours. Its dull faded fawn colored surface is rolling and tumbling in waves several feet high, and there is a swift current cutting under the wave washed banks. The water is so high and the banks so low, that we are on a level with the monotonous flat plain stretching away in all directions. Here and there indeed the plain is lower than the river’s surface and the water is restrained by a low dyke. The soil is exactly the same color as the water and is baked as hard as bricks in the sun’s heat. The Arab peasants scratch the surface in crooked striations with a pitiful wooden plow and gather a good crop but only a fraction of what might be expected from a soil and climate like these.

Shatt el-Hai: Reed rafts supported by inflated bladders of sheep or goats (kelek keset). (N. 3505, P. 7065)

Shatt el-Hai: Reed rafts supported by inflated bladders of sheep or goats (kelek keset). (N. 3505, P. 7065)

Shatt el-Hai: A view of a village along the shore of the stream. (N. 3525, P. 7085)

Shatt el-Hai: A view of a village along the shore of the stream. (N. 3525, P. 7085)

Shatt el-Hai: A sacred tomb on the shore. (N. 3526, P. 7086)

Shatt el-Hai: A sacred tomb on the shore. (N. 3526, P. 7086)

Along the banks are occasional little groups of round topped huts, with walls of mud and roofs of reed matting carried over like a barrel vault. Numerous flocks of sheep and goats straggle far across the plain and find a scanty patch of grass now and then, among long stretches of dusty bare hardbaked earth. The women and children leave the flocks and come running out of the huts to gaze curiously at our launch. Frequent groups of Arabs with garments girded up around their loins stand waist-deep in the mouths of irrigation trenches by which they lead the waters to their fields. They are armed with long-handled spades and hoes which they wield lustily in repairing breaches, building dykes or deepening the trenches. Now and then we pass chunky reed rafts standing high out of the water, with a black robed Arab and his black robed harim perched on its top. He has much difficulty in keeping his clumsy craft from driving ashore in the heavy cross wind, by spasmodic use of a curious pole made of reeds bound together. The stream is only 300 to 400 feet across, and being in color almost exactly like the low plain on either hand the result is a deadly monotony of landscape stretching in ignoble flatness from horizon to horizon. Overhung as it is today by a dull grey sky but little brightens there the parched plain, nothing more forbiddingly desolate can be imagined.

The boat shakes a good deal, — the wind flutters the paper incessantly and the gas smells, — all together writing is somewhat hampered. Nevertheless I must give you a little log of our doings. We spent Wednesday the 17th (March) at Ur, as I have written you from there. The morning of the 18th (Thursday) we went out in 3 cars (Ford vans) 16 miles south of Ur Junction to Abu Shahrein, the ancient Eridu, once on the Persian Gulf, but now about 175 miles from its shores. It was a curious experience to go out bowling across the desert where once rolled the waters of the Persian Gulf, and passing Ur again, to leave as many miles of desert behind us in 1-1/4 hours as a caravan could cover in a day!

We had left our stuff in a baggage van (box car) at Ur Junction while we went out to Abu Shahrein and we found it all right on returning. Thursday evening we had it coupled on to a local freight train for Nasiriyeh, ten miles away and at 7:30 p.m. we pulled in at Nasiriyeh, having ridden very comfortably perched on our duffle bags in the box car. The commandant, Major Beaver came down to meet us with a 5 passenger Ford and a Ford van. I had sent our Basrah van (see previous letter) on from Ur Junction and it also appeared at the station. Two ox carts drew up likewise and we soon disembarked.

I had had the boys get out a day’s food in a special basket ready for the next day’s excursion, and so we left our stores all in the box car and took only bare necessities up to the town. Luckenbill and I were invited to put up with Major Ditchburn, the political officer, and the three boys were taken in by Major Beaver. It is not a little interesting to see the British administrations beginning in this remote corner of the world, especially at Shatra. Our Basrah car broke down the next morning, but I secured another from the irrigation administration through the kindness of Major Ditchburn; but it was noon before we could start on a 40 mile ride up the Shatt el-Hai to Shatra el Muntefik. Riding across the Babylonian plain in this way was most instructive. It gave us our first glimpse of Bedwin life out in the wilds. We had four cars, two vans and two five-passenger cars. Crossing scores and scores of irrigation ditches and canals often involved ticklish driving. We had our Tommy and 3 Indian drivers. The Tommy was all right, but one of the Indians finally drove one of the vans off a bridge and the entire front, engine and wheels hung over the canal. We got it back, but the steering rod was broken. We went on to Shatra (where we passed Clay but could only shake hands) and were cordially welcomed by the Assistant Political Officer, Captain Berkeley. We then sent the uninjured van back for our luggage from the broken van where Ali the cook and Abbas the camp boy were watching it.

It was nearly 4 p.m. when we sat down to lunch with Captain Berkeley. After long consultation we got a tentative program arranged by wire with the next Political Officer on the Shatt el-Hai, Captain Crawford. Berkeley then took us around the bazaar of Shatra. It is a little town of 6000 people and Berkeley has about 60,000 souls in his district. Here he rules like a king. He is only 22 years old, and the sheiks come in and consult him as if he were a sovereign. For many years the tribal troubles among the Muntefik Arabs have resulted in the killing of probably 2000 men every year (native reports), and the Turks had no control over them. No taxes had been paid by the Shatra district nor had any effort to collect any been made by the Turks for 15 years before Captain Berkeley took charge. One turbulent old Sheikh alone has paid Berkeley 60,000 rupees (about $25,000) taxes and Berkeley is now collecting 300,000 rupees yearly from the district. He has built a neat headquarters for his offices at a cost of 15,000 rupees, with cells just by the door, where I saw two political offenders incarcerated. It would interest you to see a young Englishman of about your age gravely showing us his new roofed market building for women, and the arrangements he has made for cleanliness in the general market. I cannot tell you half of the interesting things we saw here, winding up for tea at the house of Said, a wealthy merchant, where all the leading men of the village followed us in and we sat gravely talking for an hour.

Shatra: Looking a little west of south from the roof of Berkeley’s house at Shatra. The tower is the minaret of a mosque. Notice the little balcony encircling the tower, that is where the muezzin stands when he calls the hour of prayer. March 19, 1920. (N. 44618, P. 65845)

Shatra: Looking a little west of south from the roof of Berkeley’s house at Shatra. The tower is the minaret of a mosque. Notice the little balcony encircling the tower, that is where the muezzin stands when he calls the hour of prayer. March 19, 1920. (N. 44618, P. 65845)

Shatra: Looking north from the same point as the previous picture, on the roof of Berkeley’s house at Shatra. The street turns so that you look straight down it. The Shatt el-Hai comes round a bend in the middle distance and flows out of the picture at the right edge. March 19, 1920. (N. 44619, P. 65846)

Shatra: Looking north from the same point as the previous picture, on the roof of Berkeley’s house at Shatra. The street turns so that you look straight down it. The Shatt el-Hai comes round a bend in the middle distance and flows out of the picture at the right edge. March 19, 1920. (N. 44619, P. 65846)

Shatra: Berkeley’s house, court, north view along west wall; Ludlow S. Bull standing. March 19, 1920. (N. 44621)

Shatra: Berkeley’s house, court, north view along west wall; Ludlow S. Bull standing. March 19, 1920. (N. 44621)

Berkeley’s cook made our visit the occasion for getting frightfully drunk and we fared badly as to food. Next morning (Saturday, March 20), we started early for Tello, the ancient Lagash. The king who drilled the phalanx shown in my Ancient Times ruled here. Berkeley’s launch was out of order and we had to take a native boat (bellum) and pole or tow upstream for over an hour to a point where Berkeley had arranged for horses to meet us. There was some difficulty in picking out the equine victim which was to carry Luckenbill’s 215 pounds! Off we rode at last, and were soon out among the irrigation trenches and canals which often cost us long detours. It was not until nearly one p.m. that we rode in among the ruins of Tello, the mounds of which we had seen for two hours before we reached them. Indeed we could discern them the evening before from the roof of Berkeley’s house by careful use of the field glass.

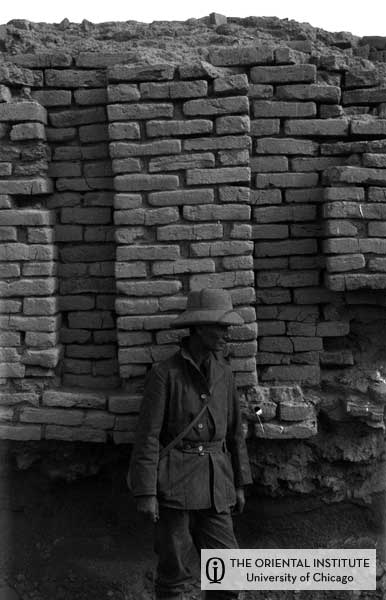

Tello: Gudea’s Wall and its foundation. March 20, 1920. (N. 44632, P. 65858)

Tello: Gudea’s Wall and its foundation. March 20, 1920. (N. 44632, P. 65858)

Tello: North face of Parthian Palace and W. Arthur Shelton in the foreground. March 20, 1920. (N. 44634, P. 65860)

Tello: North face of Parthian Palace and W. Arthur Shelton in the foreground. March 20, 1920. (N. 44634, P. 65860)

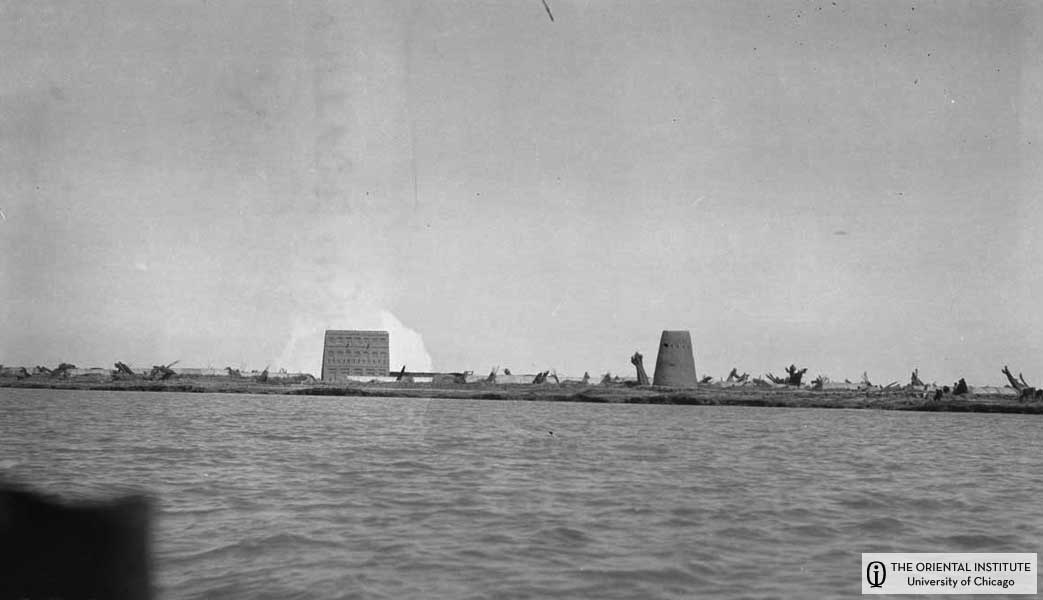

Tello (ancient Lagash): Remains of the palace and the Parthian structure. March 20, 1920. (N. 3185, P. 6745)

Tello (ancient Lagash): Remains of the palace and the Parthian structure. March 20, 1920. (N. 3185, P. 6745)

Tello (ancient Lagash): An Arab plowman with his animals. March 20, 1920. (N. 3188, P. 6748)

Tello (ancient Lagash): An Arab plowman with his animals. March 20, 1920. (N. 3188, P. 6748)

We lunched on the highest mound, while our two Arab guards, sent with us by Captain Berkeley, sat watching our horses, with their rifles over their knees. Tello is the most extensive place we have visited, but it is very disappointing. There is only one building of burnt brick of which any superstructure survives,—a Parthian palace built of brick taken from a much older palace of the famous viceroy Gudea. Gudea’s bricks are numerous, all stamped with his name. Indeed the court of Berkeley’s house (not built by him) is paved with bricks bearing Gudea’s name. But the sombre mounds of his town are at least 1/4 mile long, and traces of houses extend far out into the plain, especially on the southwest side, as we noted in approaching from that side.

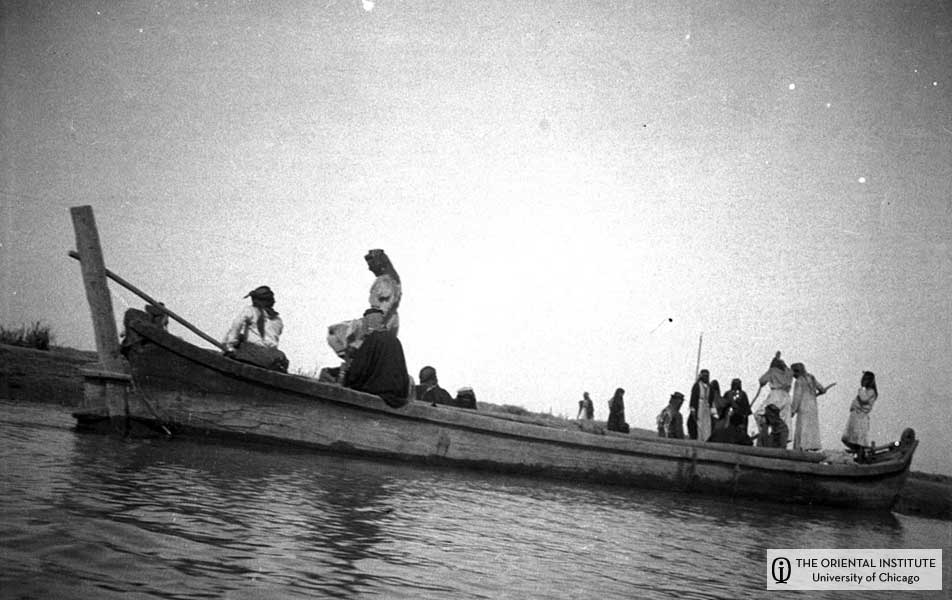

It was nearly 4 p.m. when we mounted our horses again and set out for the river, going almost exactly westward. The water and the canals delayed us somewhat. I had sent Ali and Abbas and one Arab guard up the river in a large bellum as we left Shatra, with instructions to ascend the stream to the village of Suwej (or Suwedj) ibn Sagbân, or Suwej ibn Sirhan, which is nearly opposite Tello, and to pitch the tents and get dinner.

Shatra: Rudder and helmsman of the boat which carried our baggage up the Shatt el-Hai. Photographed from the shore at Shatra. March 20, 1920. (N. 44625, P. 65851)

Shatra: Rudder and helmsman of the boat which carried our baggage up the Shatt el-Hai. Photographed from the shore at Shatra. March 20, 1920. (N. 44625, P. 65851)

Shatt el-Hai: Boat which carried our baggage up the Shatt el-Hai from Shatra to Suwêj. March 20, 1920. (N. 44628, P. 65854)

Shatt el-Hai: Boat which carried our baggage up the Shatt el-Hai from Shatra to Suwêj. March 20, 1920. (N. 44628, P. 65854)

As we neared Suwej I saw an Arab horseman approaching. And as I was at the head of the column, he rode up, shook hands and gave us a cordial welcome. He was the sheikh of Suwej, a fine looking Arab, who sat his horse like a prince—Sajed ibn Sagbân. As we approached the village chatting I saw our tents pitched close to the river. All the town gathered about and contemplated our proceedings as we set up our field basins, sent the servants for water, and washed up in river water dirtier than we were!

Ali now came and said he had no dinner ready, — the Sheikh Sajed had invited us to a repast at his house. So just at dusk, Sajed’s servants appeared and served coffee beside our tents. As we drank it began to rain and we therefore followed Sheikh Sajed to his house. He cleared the little streets or lanes before us, cuffing now and then an overcurious boy or girl, and we swept through the village in great state. Sajed led us to a spacious Mejlis tent, at least 50 feet long and high in proportion, entirely open on one of the long sides and roofed with dark camel’s hair tenting. A bright fire was burning on a large low clay hearth in the middle of the tent. Facing it down each of the long sides sat the leading men of the village, who rose at once as we entered. I greeted them as best I could and they responded courteously. One usually says “Salâm alêkum” on entering a dwelling and the household respond “Alêkum es-Salâm”. We were led to the far end of the tent where rugs and cushions were spread. I was put down with space for my party on my own right and a single vacancy on my left, intended of course for the host. I asked him, as he remained standing to take this seat, but he politely refused, on being pressed, said he was my servant, (Ana Khidmatak) more literally, “my servitude”. Of course I was expected to repeat the invitation, which I did, and this procedure having been repeated several times more, our host at last sat down, as he was intending to do all the time.

It was a striking scene before us as we were all at length seated. In the middle the servants prepared coffee on the clay floored hearth surrounded by gleaming brass utensils, and on each side were ranged in two long lines the village notables, picturesque enough in their native dress. The flickering firelight touched the kuffiya draped heads, and ample abbas (cloaks), among which swarthy faces and gleaming dark eyes watched us expectantly while over all spread the dark canopy of the lofty camel’s hair tent roof. Coffee was served several times, and the sheikh himself plied us with cigarettes of his own making, which he insisted on lighting. Our servant Abbas then came to me and asked in a whisper, if I would like to have him bring forks and knives from our tent. I told him no, we would eat as our host did. He said, “With your hand”! and I said, “Yes indeed”. A huge round dish a yard in diameter piled with rice cooked with raisins was then brought before us and placed on a rug on the floor. Many small dishes each bearing a whole roast chicken or pieces of roast mutton were then ranged round the rice, together with a flat dish of sweet cereal pudding for each guest. Much urging only at length induced the host to seat himself with us. He broke into quarters large pancake like loaves of Arab bread at least a foot in diameter and with these pieces of bread to aid us we fell to like brave(?) trenchermen for we were hungry. We are nearing our destination and I cannot go on with the Arab supper.

Kalat es-Sikkar: Arab reception of Mitlak, successor to Mizil. (N. 3192, P. 6752)

Kalat es-Sikkar: Arab reception of Mitlak, successor to Mizil. (N. 3192, P. 6752)

Kalat es-Sikkar: Arab women, wives of Mizil, running up to Captain Crawford to intercede for the deposed sheikh. (N. 3195, P. 6755)

Kalat es-Sikkar: Arab women, wives of Mizil, running up to Captain Crawford to intercede for the deposed sheikh. (N. 3195, P. 6755)

Kalat es-Sikkar: Reception of Mitlak, successor to Mizil. (N. 3516, P. 7076)

Kalat es-Sikkar: Reception of Mitlak, successor to Mizil. (N. 3516, P. 7076)

Kalat es-Sikkar: Arab reception of Mitlak, successor to Mizil, at entrance to tent. (N. 3705, P. 7265)

Kalat es-Sikkar: Arab reception of Mitlak, successor to Mizil, at entrance to tent. (N. 3705, P. 7265)

On entering the village I was met by a native messenger from Captain Crawford, saying he had sent his launch down to meet us and we could come up to him this morning. Sheikh Sajed appeared at our tent at daylight with eggs and bread, and we soon had all our stuff on board the launch. It is a big staunch craft nearly 50 feet long, and we are lucky it is for this wind would capsize a smaller boat. There is a violent sand storm raging, and our eyes and ears are full of dust. Blinding clouds of sand and desert dust are driving across the river and far across the plain, obscuring the palms of Kalet Sikkar which we are now nearing, the only palms, with one exception, which we have seen since leaving Shatra yesterday.

The name of the place is really Kal’at es-Sikkar, “the fortress of Es-Sikkar” as there was once a stronghold here. The local people all pronounce the initial K soft like j, i.e., jal’at or shortened jil’a.

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577