Tibni Khan, Upper Euphrates

May 7, 1920

I was interrupted by the above necessity of calling on the Pasha first, lest he be offended by my calling on any one else before I came to see him. So I dropped the type-writer at once, sent out to determine where the Pasha was, and found he was at his desk in the serial. — So thither Luckenbill and I sallied forth, and were at once ushered into the great man’s presence. He was a young, fine-faced Arab seated at a desk and appearing incongruous enough in his picturesque desert attire, thus framed behind a desk. A number of waiting natives on the divans watched us curiously, and listened attentively to our greetings and our story, and especially to a long oration in the finest Arabic by the Pasha on the state of the new Arab nation, and the difficulties confronting it. It was an interesting scene, but I was anxious to get our future plans arranged. As soon as I properly could I asked him about Nadji Beg Suwedi (Suwedi being really the father’s name). I had heard all sorts of whispers about him and did not know why he had really come up to Der ez-Zor. I therefore asked the Pasha frankly whether it was proper for me to call on Nadji Beg and ask about our further journey to Aleppo. The Pasha said certainly that he himself would send soldiers with us, but that Nadji Beg was going to return to Aleppo the next morning, in all probability, and that we could go with him. The Pasha then sent a messenger for Nadji Beg, who presently appeared, and expressed great pleasure at receiving a letter from his father which of course I had at once handed to him. He told me he would be leaving for Aleppo in the morning, and would be very much pleased to have us go with him, expressing only some apprehension lest our three baggage wagons should be unable to keep up with him, as he expected to make the trip to Aleppo in four days. Luckenbill and I then took our leave and walked for half an hour along the Euphrates, here divided by a large island, connected on both sides with the mainland by a bridge and filled with beautifully green and luxuriant gardens.

On returning to our lodging, our Mohammed announced a visitor, who appeared in the person of a handsome young Arab officer. He at once began to talk about the Arab State and the much desired assistance of America. Before we had gone very far, four more officers appeared, quite filling our little bed room. Their leader introduced the others by name and title and said they had come to discuss with me the political future of the Arabs, because they had such confidence in America and such admiration for the great republic, whose aid they so much needed. I was really touched by their earnestness and their childlike eagerness for light and for information regarding the intentions of the British. Everybody in town had been delighted at the information I brought that the British were going back nearly a hundred miles. The news went from lip to lip, and we were regarded almost as the official messengers who had brought it. I had hoped for a few minutes in which to tidy up my travel-stained khaki outfit, but the visitors stayed on until the colonel, the officer who had first called, told them we were momentarily expected by the Pasha and must go. Indeed he had been sent to show us the way to the Pasha’s house. The leader of the group then asked if they might come again, and when I had explained that we were obliged to leave the next morning under Nadji Beg’s safe conduct, they showed the deepest disappointment, and went away quite cast down. We then walked quickly to the Pasha’s house where we found all prepared to receive us. It was 7:30 P.M., and while coffee was served and the cigarettes passed frequently around, we talked with the Pasha and his officers, of whom half a dozen straggled in after us. They all wanted to talk about their country and its need of help, which they begged me to say, when I reached home, was eagerly expected from America. They all expressed not only admiration but affection for America and complete confidence in our ability to help them. I confess that this wide-spread respect for our country this general expectation of help which it was sure to send, threw a new light on our responsibilities. The world was everywhere expecting great and new things from us. We too were ready and eager to furnish new light and direction. We failed because of totally inadequate leadership. I tried as best I could to explain to them our own difficulties, but I could not make them see it. We were so tremendously powerful, we had such unlimited wealth, we were the land of liberty and human rights, where all men were treated justly and fairly; surely we could secure—or help to secure—the same things for the Arabs who had so long endured pure despotism.

They told me of Feisal, now proclaimed king of Syria, of his father king of the Hejaz, and of his brother Abdullah, proclaimed king of Iraq (Babylonia and Assyria), a proclamation which the English had at once disavowed and disallowed. They showed me their new flag and explained the meaning of its colors, and gave me one printed in colors on paper. An hour had passed before any one had thought of dinner. The Pasha led the way, and as usual insisted I should take the seat of honor at the head of the table, an honor which as usual I had persistently to refuse in his favor. The dinner was good and very welcome after the kind of fare we have been furnishing ourselves. The Pasha was pale, with refined spiritual features, which showed suffering, and on my noting that he ate scarcely anything, he said he had been through a long sickness and was only that day out of his bed. The dinner talk was again almost entirely devoted to the future of the Arabs. The Pasha had been the first Arab officer to go out with Lawrence whose report I have sent you, and while he expressed appreciation of Lawrence and of the fine qualities of the English, he said the English must necessarily serve their own state and people, but he must likewise serve his. What they wanted was for the English to go and leave the Arabs to run their own affairs, hoping for the guidance and advice of America, until the new Arab nation, after centuries of strife and disunion, could gather strength, gain experience and deserve a place with the other nations of the world. They all expressed deep seated resentment toward the British, and unconquerable determination not to permit English domination. It was, I assure you, a great surprise to me, and I believe it would be equally so to the British statesmen now guiding the British Empire.

Nadji Beg came in after we had left the table and we made the last arrangements for a start at the earliest possible moment in order to make Aleppo in four days. We left the Pasha with regret, and I am very sorry that we failed to secure a snap shot of him. On reaching our lodgings, I found Mohammed, Leachman’s former servant, who had come to Der with us, was waiting for me with another man-servant to go with us all the way to Aleppo, as he (Mohammed) was obliged to go back to Abu Kamal to rejoin Colonel Leachman, I told Mohammed of our arrangements for an early start, and charged him to see the drivers and make them understand they must be on hand with all five wagons at 4:30 the next morning. I was very anxious to be prompt, for it had been a vast relief to know that the safety of the party all the way to Aleppo would be guaranteed by Nadji Beg’s presence and assistance. Mohammed said he would surely attend to it, and as it was late and I was very tired, with a short night before me I let it go at that.

I was out at 3:45 and aroused the party. The new servant Ibrahim, who had told me he would sleep in the house, was not to be found, much to my indignation; for I wanted to send him for the wagons. To make a long story short, we got our things down into the street, and waited till nearly six o’clock for those scoundrelly drivers, who had been duly told by Mohammed, just what I had charged him… However, we got off at last, Nadji having long before sent me word that he would wait for us at Tibni, 31 miles away, and that he would go on ahead in order to avoid driving in the heat. We had constant trouble with the drivers, who had evidently been making a night of it in the town. They all went to sleep on the box, and we loafed along at 2-1/2 miles an hour. Toward noon we passed the tents of a large tribe of Bedouin, the Albu Hayyal, and the Sheikh sent out a messenger to urge us to come in and have coffee. I thought it best to accept, and we walked over to the big black nadhif (guest-tent) where the sheikh gave us a cordial welcome, and asked me warmly after our welfare and that of America. “For” said he, “we Arabs all love America, and without America, the English and the French could not have won the war”. “Well”, said I, “the war is over now”. The sheikh looked at me shrewdly and said, “Between the Arabs and the English?”. Whereupon there was a loud murmur of approval from the old men, and some score wild looking Arab rifles, who sat around the big nadhif. We chatted on, the sheikh assuring me again that the Arabs loved America, an assurance that was very welcome as I looked about and realized that we were there alone in the heart of the Arab world of western Asia, deep in the vast Euphrates wilderness without a soul who could have raised a finger to help us. They spoke approvingly of the American flag on our arabanah, saying it was the first one they had ever seen.

Deir ez-Zor: The Oriental Institute expedition caravan at a sharp turn near the town. (N. 3845, P. 7405)

Deir ez-Zor: The Oriental Institute expedition caravan at a sharp turn near the town. (N. 3845, P. 7405)

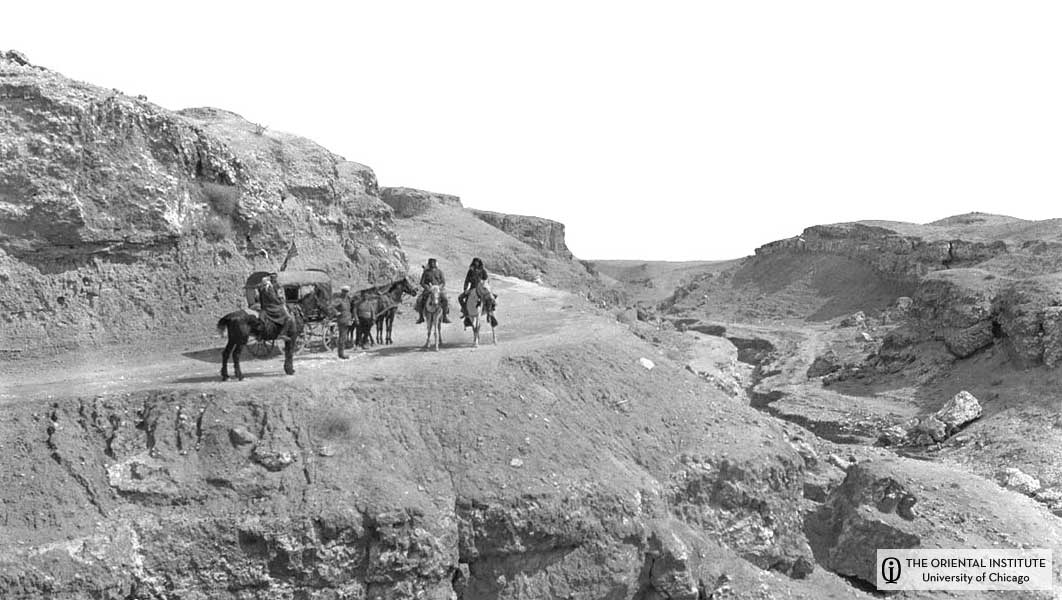

Deir ez-Zor: Cliffs of the desert plateau north of the town; the Oriental Institute caravan is in foreground. (N. 3852, P. 7412)

Deir ez-Zor: Cliffs of the desert plateau north of the town; the Oriental Institute caravan is in foreground. (N. 3852, P. 7412)

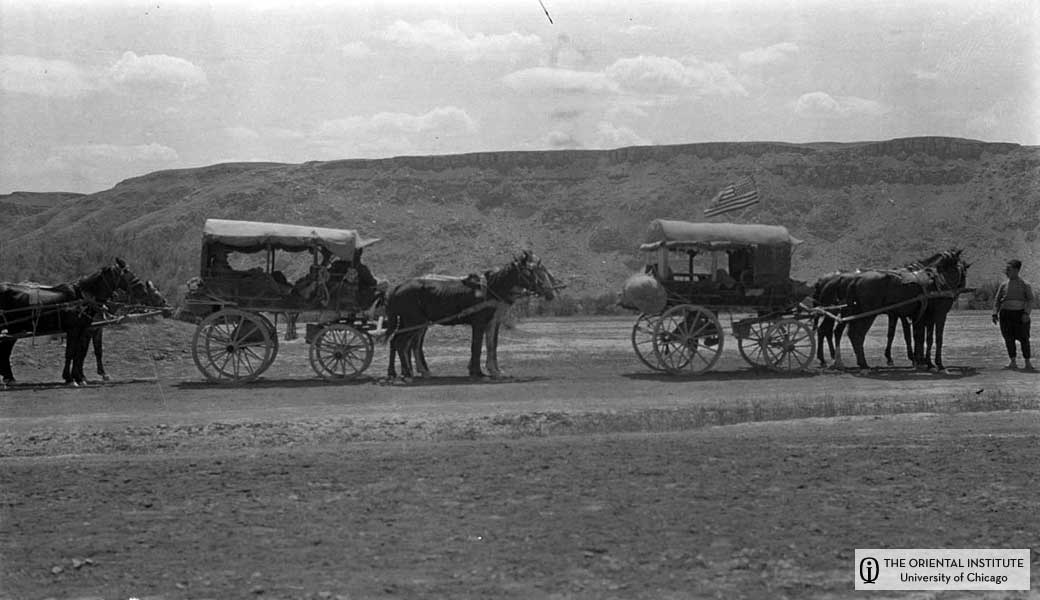

Deir ez-Zor: A view of the plain north of town, showing tents in the brush at left and the wagoon of the Oriental Institute party at right. (N. 3854, P. 7414)

Deir ez-Zor: A view of the plain north of town, showing tents in the brush at left and the wagoon of the Oriental Institute party at right. (N. 3854, P. 7414)

After the coffee had gone around twice, I suggested that we be allowed to take a picture of the assembled Arabs, and they all assented with evident pleasure, for the Arabs loved to be photographed. So we lined them all up in front of the big black tent, and Luckenbill snapped them all several times, the Sheikh absolutely refusing to stand at my side and be taken with us, — evidently because of an injury to his nose, which had carried away a part of it.

Deir ez-Zor: Arab followers of Ramadan in front of sheikh’s tent. Professor Breasted, Messrs. Shelton and Bull at left. Green banner in the center. (N. 3846, P. 7406)

Deir ez-Zor: Arab followers of Ramadan in front of sheikh’s tent. Professor Breasted, Messrs. Shelton and Bull at left. Green banner in the center. (N. 3846, P. 7406)

Deir ez-Zor: Arab followers of Ramadan in front of sheikh’s tent. The sheikh is at the left with back turned. Professor Breasted, Mr. Shelton, and Mr. Bull are also at the left. (N. 3848, P. 7408)

Deir ez-Zor: Arab followers of Ramadan in front of sheikh’s tent. The sheikh is at the left with back turned. Professor Breasted, Mr. Shelton, and Mr. Bull are also at the left. (N. 3848, P. 7408)

Deir ez-Zor: Tribesmen of the Albu Sarai. (N. 3850, P. 7410)

Deir ez-Zor: Tribesmen of the Albu Sarai. (N. 3850, P. 7410)

As we crowded back into the tent, a huge Arab with a massive tent-mallet in his girdle raised it over my head. I thought for an instant that we were in trouble, but the Arab explained that was what he would do if I were an Englishman, and as he did so smote the ground several times with all his strength, saying that was how he would treat the English if he got a chance! As I took my leave and thanked the sheikh for his hospitality, he stopped me and told me he had an important letter which he wished to send to Aleppo addressed to a newspaper there. He said he knew he could trust an American to deliver it. I said certainly, and one of his servants at once brought the letter which the sheikh handed me while all the assembled Arabs stood watching in silence as I laid it carefully into the beautiful wallet which Charles gave me. The Sheikh accompanied us to the arabanahs, and directed one of his riflemen to mount beside one of our drivers and accompany us to the next khan. [*His name was Ramadhan Beg Shilash, and his tribe are the Albu Hayyal.]

When we arrived at Tibni it was so late that Nadji Beg had already gone to the next khan, leaving a soldier to explain that if we left at dawn the next day, we could still overtake him. At first I demanded the drivers should make good their tardiness of the early morning and go on to the next khan. But when I learned it was nineteen miles away, I gave it up.

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577