Planning the Identical Lunch

By Emily Capper

University of Chicago PhD candidate and Smart curatorial intern

Feast has been open for more than a couple of months, yet the parts are still moving. An exhibition of more traditional artworks would have been entirely settled long ago. It's of course true that paintings and sculptures change something of their appearance and meaning when installed under particular physical and discursive conditions -- against a brightly colored wall or next to an explanatory label, for example. But with Feast, we're involved in a qualitatively different situation. Several works in the show simply did not exist in physical form until now. We have been actively generating these forms in literal collaboration with artists -- and they're not finished yet!

Take, for example, Alison Knowles' Identical Lunch. Although dated 1969 according to museum convention, the work has no clear-cut origin, and has changed form -- and identity -- over time. Indeed, that's the chief philosophical point of the Lunch: that no object is identical to itself in human experience. Knowles tells us that the project began unconsciously, as just something she did (and not yet "art"). Throughout the late sixties she visited the same neighborhood luncheonette at noon and ordered the same meal (the best thing on the menu, she recalls). With her friend, the composer Philip Corner, Knowles came to think of the lunch as a semi-formal performance, and so she published a score, which reads:

"The Identical Lunch: a tunafish sandwich on wheat toast with lettuce and butter, no mayo, and a large glass of buttermilk or a cup of soup was and is eaten many days of each week at the same place and at about the same time."

Like a musical score, this one inspired and guided countless performances of the lunch. Her friends participated, recording their diverse experiences of the "same" meal through a network of texts and snapshots.

Such creative "documents" are easy enough to present in a museum context, and Feast includes wonderful examples of this material, like a suite of screenprint portraits Knowles made of her friends eating the lunch. But early on in the curatorial process we sensed the limitation of this approach. It places Knowles' project securely in the past, when in fact as an artist she's committed to the possibilities of the present.

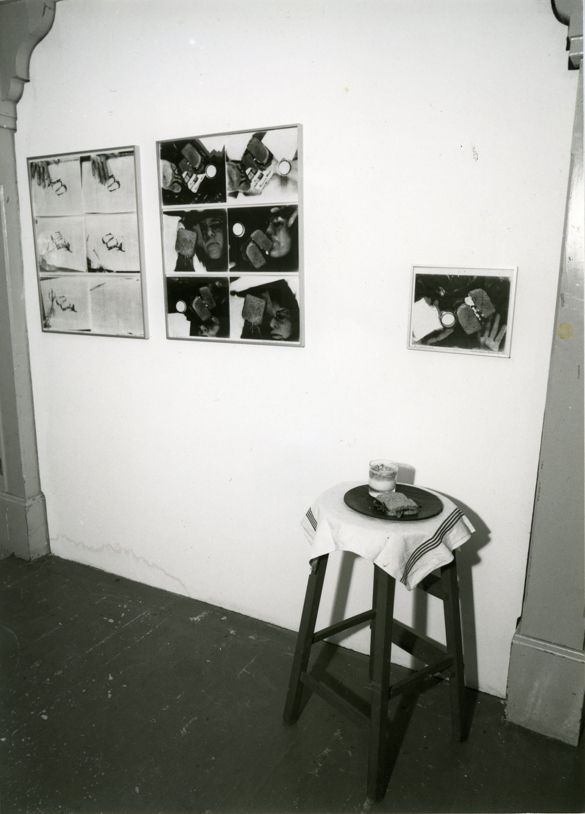

How, we wondered, could we be faithful to this aspect of the work? How could we make contingency palpable in the finite and necessarily regulated space of the gallery? Sarah Mendelsohn and I brought these questions to Alison herself in a series of fascinating conversations. Together, we decided to revisit an installation form pictured in an anonymous snapshot from the 1970s (above).

We placed a wooden counter stool in the gallery with a simple cloth napkin and plate on top. Several times a week, our Security Supervisor Paul Bryan fills that plate with a real glass of buttermilk and a tunafish sandwich prepared fresh by Foodism, a local caterer, according to the specifications of Alison's score. Several days later, when the sandwich and buttermilk are just on the verge of going bad, Paul replaces them again. Through this ongoing ritual, which depends on so many people, visibly volatile food enters the gallery and provokes visceral reactions that range from hunger to disgust (depending on the visitor's taste).

Of course, the viewer can't eat this sandwich, which is secured under a plastic cake cover. But just outside the gallery she's invited to perform the score -- even daily, if she wishes. The Museum café stocks the Identical Lunch made by Foodism for purchase, like any other item on the menu. Along with the tunafish sandwich, you can choose a glass of buttermilk or a cup of the soup of the day.

This Saturday (May 5) we are all invited to ingest the Identical Lunch in yet another form. As part of the Of Hospitality symposium, Alison will be directing student volunteers (including me and Sarah) to perform her new Identical Lunch Symphony. Alison based the symphony's score on her friend and Fluxus colleague George Maciunus' 1971 interpretation of her 1969 score, which he set down in a letter: "Dear Alison, Here is my idea for the--identical lunch--Put tuna fish, wheat toast, lettuce, butter, soup or buttermilk--all into blender--blend till all is smooth--drink it. Best regards, George."

Alison's Symphony further processes Maciunus' idea for the lunch through the idiom of formal concert music. The student volunteers will be the orchestra and our personal blenders will be our instruments. While mass-produced, no two blenders sound identical. Inspired by the unpredictable range of sounds at her disposal, Alison will assume the role of conductor. She'll direct each of us to variously and rhythmically crush, mix, and puree the sandwich with a quart of buttermilk "till all is smooth." We will then offer it in cups to the audience. When Alison first told us about her plans for the symphony, I couldn't help but pucker my lips in almost instinctual disgust.

She assured us, though, that blending the lunch in fact transforms it into "a wonderful cold fish soup." I cannot wait to test this theory in experience on Saturday.