By Diego Arispe-Bazan

MA'11 University of Chicago and Smart curatorial intern

At a salon hosted by threewalls a few weeks ago, with a group of artists, sociologists, and other practitioners working on various social engagement projects (including Martha Bayne of Soup and Bread and the Smart Museum's own Stephanie Smith), the conversation turned for a moment to the possibility of productive failure. Martha shared a story. Once, at a Soup and Bread event, she was chastised by a visitor for the lack of vegan options, something she had no control over, as meals brought for each iteration are donated, and their contents are up to each cook. It seemed draconian on the one hand to demand that cooks produce vegan soups; it seemed draconian, on the other, to deny vegans the ability to participate. Not providing vegan soups, a type of institutional failure, is an example of the inability to accommodate, to welcome the guest or viewer into the situation via our sensory or aesthetic offerings. However, these conflicts provide a gateway into exploring a crucial aspect of hospitality: failure to lunch.

I considered Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin's famous phrase, currently displayed in the Feast exhibition: "to invite people to dine with us is to make ourselves responsible for their well-being for as long as they are under our roofs." Hosting, therefore, is not purely about providing good food, but rather providing a good meal. When we unwittingly serve our guests a dish they find atrocious, we, as good hosts, don't simply give up. We don't blame them for their lack of taste. We don't have a hearty chuckle and keep eating as if nothing was the matter. Instead, as obliging hosts, we redouble our efforts: we offer something else, ask the guest to explain her opinion. Hopefully, we laugh together. Blatant failure, forcing a new exchange in order to overcome the impasse, leaves both guest and host with a new set of relational tools to deal with disappointment, discomfort, etc. in their social repertoire.

Yet there is still an insistence, and expectation of success. At threewalls, social workers, anthropologists and sociologists involved in participatory projects wondered: "will the communities we choose to work in respond positively--will they eat what we're serving?" How can the success of projects like Occupy Yr. Home or even the International Dinner Party, be measured?

The National Bitter Melon Council, for example, has come up against this question repeatedly. In their manual, they preemptively warn us about the bitter taste of the bitter melon fruit, a symbol and material in much of their work. In one of the texts in the NBMC's Better Living Through Bitter Melon Manual, Louisa McCall, Program Director of the LEF Foundation (2000-2008), poignantly remarks: "to what extent did we need aesthetic outcomes from art projects?" It seems to me that there is inevitably an aesthetic outcome, just as every meal has an olfactory and gustatory outcome. And they are comparable: they can be imperceptible, subtle, they can dissipate quickly or spread wildly in multiple directions. And of course, they can be colossal failures.

Ultimately, the gesture is key. We prepare our dream meal just as orchestrating participatory pieces in new communities -- we do so at the peril of our confidence. But in the common adversity of the failure, a shared, learned practice of generosity emerges, a conversation between hosts and guests, artists and audience, impossible without the gesture's extension.

Theaster Gates shows how creating intentional space for community can drive artistic discourse, through the construction, layout, and use of the Dorchester Projects house, home to the Soul Food Pavilion dinners.

Michael Rakowitz talks about serving dinner on flatware looted from the palace of Saddam Hussein. Paper replicas of these plates are being used by the Enemy Kitchen food truck, now serving Iraqi cuisine on the streets of Chicago.

If you didn't have a chance to try Enemy Kitchen's wares at the Feast opening, catch the truck in action by following the project on Twitter.

This past weekend at the Symposium, and throughout the run of Feast, people have been getting a taste of a particular tradition of Serbian hospitality: a spoonful of a sweet strawberry preserve called slatko, as a part of Ana Prvacki's Greeting Committee project.

Here, Prvacki reveals the family history behind her artistic interest in this practice.

Feast artists Marina Abramović, Sonja Alhäuser, Mary Ellen Carroll, Theaster Gates, Mella Jaarsma, Alison Knowles, Suzanne Lacy, Lee Mingwei, Laura Letinsky, Tom Marioni, Ana Prvacki, and Michael Rakowitz reflect on hospitality.

By Emily Capper

University of Chicago PhD candidate and Smart curatorial intern

Feast has been open for more than a couple of months, yet the parts are still moving. An exhibition of more traditional artworks would have been entirely settled long ago. It's of course true that paintings and sculptures change something of their appearance and meaning when installed under particular physical and discursive conditions -- against a brightly colored wall or next to an explanatory label, for example. But with Feast, we're involved in a qualitatively different situation. Several works in the show simply did not exist in physical form until now. We have been actively generating these forms in literal collaboration with artists -- and they're not finished yet!

Take, for example, Alison Knowles' Identical Lunch. Although dated 1969 according to museum convention, the work has no clear-cut origin, and has changed form -- and identity -- over time. Indeed, that's the chief philosophical point of the Lunch: that no object is identical to itself in human experience. Knowles tells us that the project began unconsciously, as just something she did (and not yet "art"). Throughout the late sixties she visited the same neighborhood luncheonette at noon and ordered the same meal (the best thing on the menu, she recalls). With her friend, the composer Philip Corner, Knowles came to think of the lunch as a semi-formal performance, and so she published a score, which reads:

"The Identical Lunch: a tunafish sandwich on wheat toast with lettuce and butter, no mayo, and a large glass of buttermilk or a cup of soup was and is eaten many days of each week at the same place and at about the same time."

Like a musical score, this one inspired and guided countless performances of the lunch. Her friends participated, recording their diverse experiences of the "same" meal through a network of texts and snapshots.

Such creative "documents" are easy enough to present in a museum context, and Feast includes wonderful examples of this material, like a suite of screenprint portraits Knowles made of her friends eating the lunch. But early on in the curatorial process we sensed the limitation of this approach. It places Knowles' project securely in the past, when in fact as an artist she's committed to the possibilities of the present.

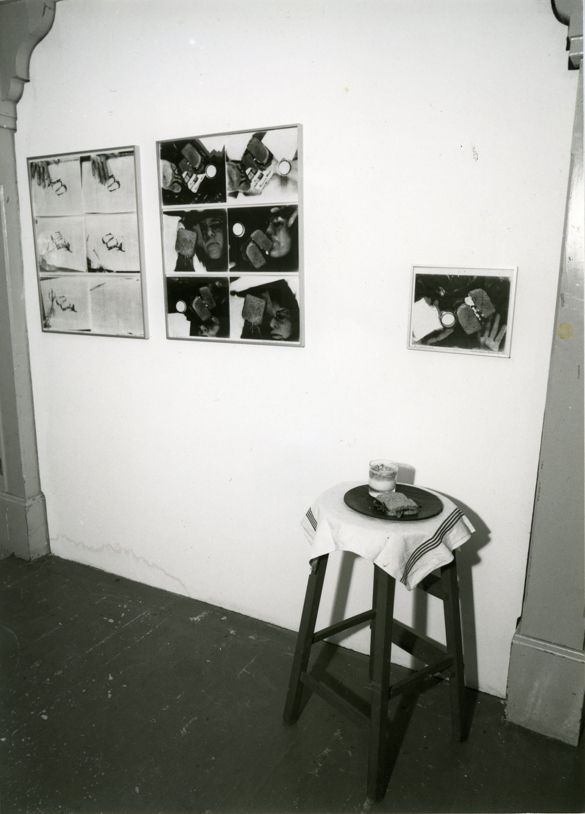

How, we wondered, could we be faithful to this aspect of the work? How could we make contingency palpable in the finite and necessarily regulated space of the gallery? Sarah Mendelsohn and I brought these questions to Alison herself in a series of fascinating conversations. Together, we decided to revisit an installation form pictured in an anonymous snapshot from the 1970s (above).

We placed a wooden counter stool in the gallery with a simple cloth napkin and plate on top. Several times a week, our Security Supervisor Paul Bryan fills that plate with a real glass of buttermilk and a tunafish sandwich prepared fresh by Foodism, a local caterer, according to the specifications of Alison's score. Several days later, when the sandwich and buttermilk are just on the verge of going bad, Paul replaces them again. Through this ongoing ritual, which depends on so many people, visibly volatile food enters the gallery and provokes visceral reactions that range from hunger to disgust (depending on the visitor's taste).

Of course, the viewer can't eat this sandwich, which is secured under a plastic cake cover. But just outside the gallery she's invited to perform the score -- even daily, if she wishes. The Museum café stocks the Identical Lunch made by Foodism for purchase, like any other item on the menu. Along with the tunafish sandwich, you can choose a glass of buttermilk or a cup of the soup of the day.

This Saturday (May 5) we are all invited to ingest the Identical Lunch in yet another form. As part of the Of Hospitality symposium, Alison will be directing student volunteers (including me and Sarah) to perform her new Identical Lunch Symphony. Alison based the symphony's score on her friend and Fluxus colleague George Maciunus' 1971 interpretation of her 1969 score, which he set down in a letter: "Dear Alison, Here is my idea for the--identical lunch--Put tuna fish, wheat toast, lettuce, butter, soup or buttermilk--all into blender--blend till all is smooth--drink it. Best regards, George."

Alison's Symphony further processes Maciunus' idea for the lunch through the idiom of formal concert music. The student volunteers will be the orchestra and our personal blenders will be our instruments. While mass-produced, no two blenders sound identical. Inspired by the unpredictable range of sounds at her disposal, Alison will assume the role of conductor. She'll direct each of us to variously and rhythmically crush, mix, and puree the sandwich with a quart of buttermilk "till all is smooth." We will then offer it in cups to the audience. When Alison first told us about her plans for the symphony, I couldn't help but pucker my lips in almost instinctual disgust.

She assured us, though, that blending the lunch in fact transforms it into "a wonderful cold fish soup." I cannot wait to test this theory in experience on Saturday.

On April 12, the Smart Museum's student advisory committee hosted

the Feast-inspired party I Eat You Eat. Over 500 University of Chicago students and prospective students dropped in to take part in the collaborative activities. In the aftermath of the event, students Mallika Dubey, Kirsten Gindler, John Harness, and Nicole Reyna convened a digital roundtable to reflect on the program's development and student life at the University.

John Harness:When we first started to plan a student program, we thought:

"Feast. LET'S HAVE A LOT OF FOOD!" And thus "Cakefest" (as I hear it was colloquially known around campus) was born.

Nicole Reyna:We went through a bunch of different ideas about cultural food-related practices and thought about having several different ethnicities of food represented. We definitely had the let's have a lot of food idea down, it was just a matter of deciding what and how it

would be served. We also thought about having a sit-down dinner, but decided against that based on logistics and the possibility of having to turn people away.

Mallika Dubey: There was significant discussion around the way people come together in

groups to eat. Do people always sit around a table? Do we pass food

from one person to another? And is food shared communally or do we tend to serve ourselves? We tossed around the idea of having people walk around to different stations for food, but we decided it would be best to serve guests some of the items, such as the falafel.

JH: I don't exactly remember where the idea to decorate the cakes

as part of the event came from...

NR: The cakes came about mostly from discussing how people could become a

part of the making of the food -- decorating being the most logistically sound way of incorporating this.

MD: The cake deserved its own station, because we chose to highlight the collaborative process in decorating and beautifying the cake. As it is, when you eat a slice of cake, you are to some degree aware that you are consuming part of the whole. In this way, it's nice to get a glimpse of the whole cake before you sit down to eat your share. Furthermore, the act of decorating a cake made it seem more like

a work of art to guests. There is an interplay of senses -- in that people are drawn to it visually, or aesthetically, just as much as they are drawn to it by their taste buds.

NR: The cakes were slightly messy, but everyone loved it! The line for the

first cutting of the cake seemed a little hectic but everything turned out well and we had plenty of people involved and excited. A lot of people were comforted by the fact that you needed little to no skill to be involved in the cake-decorating. Some people would just write their name, the name of their house, some flowers, or even just some random patterns.

MD: During our planning, we discussed how cakes are often placed

on a pedestal at weddings, bridal showers, anniversaries, etc. People always want to eat a really beautiful cake!

JH: What was fun (and terrifying) about the evening was that

we learned -- literally as we were opening the doors to let folks inside the Museum -- that the event had been advertised to all of the prospective

college students who happened to be visiting campus that day. Suddenly our expected attendance had doubled.

Kirsten Gindler: Yet in the face of this unexpected development, the Smart did not turn

students away; we welcomed them graciously and hospitably, altering the setup of the event to accommodate additional guests, which resulted in a completely enjoyable and successful event

for both current and prospective students alike.

NR: I think the fact that prospective students were there was a plus -- it showed them that our school can be fun and cool and probably brought them into the Smart Museum for the first time. It was a

little alarming when we realized just how many people we'd be having as the crowd started coming in, but we handled it well and no one (even in the crowd) seemed to feel that we were unprepared or under-resourced.

JH: Yeah, I think we handled it pretty well, mostly because we had arranged to have so much food available! It did mean that we had to change a few things on the fly -- like we scrapped the idea of passing around most of the food and instead just served it buffet style.

MD: I think the event went well for the most part. I think, however, there

needed to be more conversation triggered around the food, the ritual of eating, and the actual Off-Off performance.

NR: I heard several people talking about how the Off-Off Campus

didn't really happen. I tried to explain that it did, but it was a little "under the radar." It would've been nice

to have had Off-Off been more central to the event, but people didn't seem to be too upset.

MD: I tried explaining at the entrance to people what they were going to experiencing, but I felt that most of the time people walked in and went straight to the buffet. While they knew we were celebrating food and the act of coming together to eat, I'm not sure there was too much discussion around it. In this way, I think the cake decorating was more successful, because people were involved in decorating a part of the cake before they ate their own slice.

KG: The event reminded me that hospitality, one of the main themes discussed in Feast is one of the enduring roles of the Smart Museum in the greater University of Chicago community. I work as a barista in the café and the day after the "I Eat You Eat" event, as I served more prospective students and their parents who stopped by for snacks, I realized that the Smart really does play a unique and perhaps unsung role in welcoming people to the University. I remember my prospie visit, where I attended the museum tour with my father. We admired the collection, enjoyed espresso at the café, and he

smiled and said, "Kirsten, this place is great, maybe you will work here someday!"

NR: Especially with the opening

of the Logan Center, I'm hearing the campus in general start to talk about art more. People get really excited when the Feast exhibition comes up in conversation, mostly because it's so conceptual

and far from a traditional fine-art exhibition. The publicity and attendance of this event was a prime example of how students not often involved in the arts on campus can come in and experience what the Smart has to offer.

Mella Jaarsma: I Eat You Eat Me from Smart Museum of Art on Vimeo.

Staged previously in Bangkok, Jakarta, and Sweden, Mella Jaarsma's participatory project I Eat You Eat Me can currently be experienced in a two-person setting at the Smart Café. (Art history student James Levinsohn previously wrote about his experiences with the six-person version, and the video of that meal is currently on view in Feast.)

Here Jaarsma discusses the origins of the project in Indonesia, and the rules diners must abide by while participating. Intrigued? Our baristas will gladly furnish you with a wearable table throughout the run of Feast.

In 1996, Mary Ellen Carroll's Itinerant Gastronomy project began when the artist serendipitously acquired five hundred oysters, which were shared with friends and passers-by before a lower Manhattan storefront.

Since then, Carroll has staged meals on a construction site, in an art gallery, and on New York's High Line (pre-renovation) -- all with the intention of bringing people together for site-specific discussion and

food. In January of 2012, Open Outcry, the most recent iteration of Itinerant Gastronomy, commissioned for Feast, was staged in the Financial Gallery at CME Group, above the Chicago Board of Trade. Seated at a

custom-designed circular table able to be moved into various configurations -- a result of Carroll's collaboration with architect Simon Dance -- guests engaged in various ways with economics, art, and social justice shared food and conversation. With each of five subsequent courses came a new topic of discussion -- communication, commodity, policy, taste, and intention.

A collection of material from the history of Itinerant Gastronomy -- including transcripts, menus, photographs, a video of Open Outcry, and the specially designed seating used for its performance -- is on view with Feast through June 10.