Feast artists: September 2011 Archives

Over the last century, artists have often sought to break down the boundaries between art and everyday life--and the Smart just acquired a work of art by the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri (b. 1930) that exemplifies this way of working.

Over the last century, artists have often sought to break down the boundaries between art and everyday life--and the Smart just acquired a work of art by the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri (b. 1930) that exemplifies this way of working. In the early 1960s, Spoerri pioneered a practice that he later defined as "Eat Art." As the name implies, much of Spoerri's art centered on meals: in addition to writing and making more traditional drawings and objects, Spoerri staged banquets and created restaurant-art-projects such as the fabled Restaurant Spoerri and adjacent Eat Art Galerie in Dusseldorf. These hubs of artistic experimentation and social pleasure attracted leading members of the European avant-garde art community as well as the general public. They were also sites where Spoerri created some of his famous "snare pictures," for which the remains of an actual meal were affixed to a table and then turned sideways to create an object that hangs on the wall like a painting. A kind of readymade still life, the composition was determined by chance--the residue of consumption and convivial interaction rather than aesthetic intention.

While researching Feast this past spring, I discovered that a classic, abjectly beautifully Spoerri snare picture--made at Eat Art on June 17, 1972--was at a Swiss auction house. The Museum was successful in acquiring it and, as a result, the Smart is now one of the few US museums to own snare pictures (along with the Walker Art Center and the Museum of Modern Art). The work will be a centerpiece of Feast along with a rich selection of other material by Spoerri.

After Feast's national tour, it will return to campus as a lasting resource for research and teaching--and, we hope, an inspirational example of how artists can make powerful works out of common experiences.

Continue reading New Aquisition: Daniel Spoerri.

Feast artist Suzanne Lacy is known for engaging in projects that challenge traditional lines of division between artist and audience as well as traditional notions of artistic production and display. Lacy's lesser-known, The International Dinner Party (1979), is a perfect example of such a project. In The International Dinner Party performance, Lacy united feminist culture workers around the globe by inviting them to stage dinners that paid tribute to a particular woman in each group. By focusing on the convivial gathering as a site of strengthening personal bonds, Lacy exploded the locality and individual ownership of her creation--engaging about 2,000 women through 200 dinners that took place across Africa, Asia, Europe and North and South America during a 24-hour period. Lacy believes that projects like The International Dinner Party have the potential to transform rigid notions of art and artist because they encourage "a more subtle and challenging criticism in which assumptions--both those of the critic and those of the artists--are examined and grounded within the worlds of both art and social discourse."

Read more about The International Dinner Party and the legacy of Suzanne Lacy in Stephanie Smith's essay, "Mapping the Terrain, Again," which appeared in the Summer 2011 issue of Afterall.

Image: Documentation of Suzanne Lacy's The International Dinner Party performance, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1979.

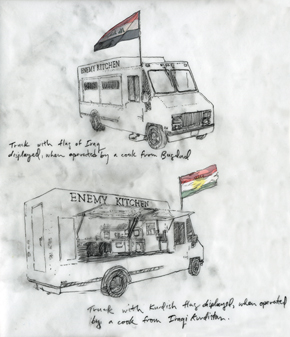

American artist, Michael Rakowitz recently shared with us a sketch of the Enemy Kitchen food truck he plans to create this winter for Feast. In the Enemy Kitchen project, Rakowitz uses his Iraqi-Jewish heritage as a point of departure for exploring food's potential to foster meaningful exchange across cultural difference.

Current plans for the food truck project involve inviting chefs from Chicago's Iraqi community to collaborate with Rakowitz on a menu, with members of the local chapter of Iraq Veterans Against the War participating as servers.

Check back for regular updates on the development and launch of the Enemy Kitchen food truck.

Image: Michael Rakowitz's working sketch for the Enemy Kitchen food truck, a commission for Feast. Courtesy of the artist.

Current plans for the food truck project involve inviting chefs from Chicago's Iraqi community to collaborate with Rakowitz on a menu, with members of the local chapter of Iraq Veterans Against the War participating as servers.

Check back for regular updates on the development and launch of the Enemy Kitchen food truck.

Image: Michael Rakowitz's working sketch for the Enemy Kitchen food truck, a commission for Feast. Courtesy of the artist.

By Jenn Sichel

University of Chicago PhD student and Smart curatorial intern

During a normal day at the museum, we all work diligently behind computer monitors and occasionally go to meetings in conference rooms. During a not-so-normal day at the museum, we might all drop what we're doing to help with a big installation. But one Friday in August, we all dropped what we were doing to head to the community kitchen at the Experimental Station to make and can 60 jars (well, 59 after I dropped one) of a traditional sweet strawberry jam called "slatko." And by sweet, I mean VERY sweet--1 1/2 kilograms of sugar for every 1 kilogram of strawberries! All of us chopped, cooked, and sealed jars together--interns, registrars, event planners, educators, curators, and even one mother-of-the-curator--it was a real family affair. The slatko we produced will be used for the Greeting Committee, an interactive, site-specific installation by Feast artist Ana Prvacki. Come February, you'll all be able to sample the sweet fruits of our labor. Literally.

Last week Ana explained to us the very personal roots of her installation that brings a new hospitality ritual to the often sterile museum environment:

I grew up with a possibly semi fictional story about multicultural manners and misunderstanding. My Romanian mother married my Serbian father and moved to Yugoslavia in 1975. There was a lot of curiosity about her arrival, family and neighbors were all dying to meet her, a young foreigner from the land of gypsies, vampires and Ceausescu, what could be more fun over coffee! Apparently they knew she was pretty but also possibly a thief, or at least very hungry and wild. And when she finally arrives she is tiny, does not speak a word of Serbian and is understandably confused by her welcoming committee standing expectantly in the doorway. Someone is holding a tray to her. She has not been informed that it contains a jar of jam like substance called "slatko", literally translated as "sweet", and it is indeed sweet, a kind of honey jam with sugar that makes the roof of your mouth vibrate. Next to it is a glass with teaspoons and a few glasses of water, the protocol being to have a spoon (or less) of the jam followed by a glass of water and then enter the household, with sweetness and welcome in ones mouth. My mother, unfamiliar with the custom and eager to make a good impression proceeds to consume the entire jar, one spoon after the other, with mmmmm's trying to sound and look delighted like any good guest should. Half way though the jar her hosts are in awe, amazed, worried, nodding to each other, she really must be hungry, they have it hard in Romania, what good sweet we make...It is unclear what happened next and I wonder if anyone tried to stop her, or if they brought out another jar. I will ask her, but I doubt she remembers clearly in her sweet delirium.

Enjoy the pictures of our adventures in slatko-making. More to follow, including a recipe!

Stephanie Smith and students of the Food for Thought course convene at the home of professor Laura Letinsky for a meal of grilled octopus, flatbread and souffle. Letinsky later discusses with students the ways in which practices of hospitality allow her to explore new themes in her art. These photos were taken by Stacee Kalmanovsky, Food for Thought TA, during last spring quarter ('11).

In an ideal world, every class would involve going to your teacher's house for lunch, and, ideally, they would make grilled octopus. Grilled octopus is delicious, but the treat isn't the whole appeal. Our class visit at Laura's served multiple functions. It provided us with a fuller context in which to situate Laura's photography practice, and to think about her use of food in photography to deal with themes of labor and time. It gave us more material for our ongoing discussion of contemporary practice and hospitality. And on a more biographical level, having lunch at Laura's apartment was a lesson in her three-year-old son's penchant for basketball, in her relationship with her cat, and, more generally, in her consideration of the relationships and boundaries between the assemblages she composes for her still lifes, and the things that frame her domestic life.

In an ideal world, every class would involve going to your teacher's house for lunch, and, ideally, they would make grilled octopus. Grilled octopus is delicious, but the treat isn't the whole appeal. Our class visit at Laura's served multiple functions. It provided us with a fuller context in which to situate Laura's photography practice, and to think about her use of food in photography to deal with themes of labor and time. It gave us more material for our ongoing discussion of contemporary practice and hospitality. And on a more biographical level, having lunch at Laura's apartment was a lesson in her three-year-old son's penchant for basketball, in her relationship with her cat, and, more generally, in her consideration of the relationships and boundaries between the assemblages she composes for her still lifes, and the things that frame her domestic life.The conversation at Laura's hinged on details: stories behind chairs or kitchen cabinets or the plates she made, about the decision to pair pistachios with slow-cooked onions on the flatbread she served with the octopus; details about family history and food, and the layered ways in which histories of recipes overlap with histories both of economy and of love. Having previously eaten as a group at Theaster's Dorchester Project, Laura made comparisons between Theaster's and her own approach to bringing people together for meals, and about taking pleasure in providing for people. As Laura's and Theaster's practices exist in different spaces, different milieus, and on different scales, the two also represent different kinds of hosts. At the Dorchester Project too there is a sense of being impressed by the personalities of things--by the bowling alley floor boards and long dining benches, the collections and archives. Their interest has to do with the breadth of resources and contributors essential to the integrity of Theaster's project. By contrast, at Laura's house the overwhelming impression is of the specificity and extent of her own daily aesthetic decisions. Where Theaster's hosting practice seems to be about projections of cultural influence, Laura's is about their internalization. Given the themes of Feast, of the course, and of Laura's practice, many of these moments take place in the kitchen: the ethic articulated by emptying the remains of wine glasses into a growing jar of vinegar on a wooden counter, or the presentation of a large soufflé following a lunch already larger than most of us are used to on a Wednesday.

There is this ideal of eating meals with professors, and of having the opportunity to see where they live, or how they live, because we want to feel that the people we are learning form are also available and receptive to us as people. Witnessing part of Laura's process of negotiating a new form in her practice has been a valuable experience for me. For her project for Feast, Laura has been working out a departure from the specific mode of photography she's been so identified with, looking to reflect on themes such as accessibility and generosity, which have long been present in her work, and to engage them from a different angle. Hosting us for lunch felt like practice.