Friday Evening

April 16, 1920

This has been one of the finest, if not the finest day we have had since we began work in Western Asia. It had not been possible to free the cars we needed on the east side of the river in time to ferry them over for our use there today, and at the last minute I was able to arrange for three Red Cross ambulances which met us at the eastern bridge head this morning.

Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Sharrukin): A view of the University of Chicago caravan and Arabs who uncovered a pavement slab in one of the gates of the walls of Khorsabad. April 17, 1920. (N. 3053, P. 6613)

Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Sharrukin): A view of the University of Chicago caravan and Arabs who uncovered a pavement slab in one of the gates of the walls of Khorsabad. April 17, 1920. (N. 3053, P. 6613)

An interesting drive of 20 miles down the east side of the Tigris brought us to the ancient city of Calah, mentioned in the Old Testament and now called Nimrûd. Early this morning I wrote a note in my best French to the old priest, the Vicar-General, who came up with us from Baghdad and whom I have mentioned several times. I asked him to go with us to Nimrûd as soon as I knew we had room enough in the cars to give him a place. When I found him this morning ready to go, he at once told me that he knew the Sheikh, Haggi Mohammed ibn-Abd el-Aziz, the owner of the ground all around Nimrûd, as well as that on which the ancient city itself stands. He urged that the Sheikh should go with us, as he would be useful now, and eventually also in the future if we ever desired to excavate at Nimrûd. I told him to drive around and get the Sheikh and meet us at the ferry. I hope I can tell you later something of the ferry at Mosul; but suffice it so say that the Christian priest and the Moslem Sheikh only a few days ago, as we now hear, at deadly enmity, duly appeared after some delay, sitting amicably side-by-side in our automobile, driving down to the ferry! With these two worthies then we drove out across the grainfields, with no trace of a road, and leaving the highway leading southward from Nineveh well to the east, we turned west over the fields toward the river on which Nimrûd evidently once lay.

We eventually pulled up, after much straining and thumping of Uncle Henry’s indispensable vehicles, alongside the temple-tower of ancient Calah. All the way out the good old priest sounded in my ears the praises of the Sheikh, telling us how many villages and towns he owned, — no less than fifteen! — and how many caravans he had robbed, and how many people he had massacred, and how his word was law for many miles around. The priest spoke French, and the Sheikh, not understanding a word, nodded complacent acquiescence to all that was said! He bore a large silver-mounted scimitar hanging at his side from one shoulder, and he told me proudly that he could trace his lineage back to the caliph Khalid, who lived in Syria before Haroun al-Rashid. The people of the region certainly bowed to his every word. We pulled up at some Beduin tents alongside a forsaken village completely devastated by the Turks during the war, and the people came out at once with milk for us, and they sent messengers to the Sheikh’s home at Balawat with instructions to prepare a banquet for us there against our arrival late in the afternoon.

Meantime we were to work at Nimrûd. We found the temple-tower in better preservation than any we had before seen. The lower terrace deeply covered with disintegrated sun-dried brick, was faced with excellent stone masonry, a thing unknown in Babylonia. Haggi Mohammed, our Sheikh, had carried on large operations here, and had quarried out one whole corner of the monument, the blocks thus obtained being laid in long rows preparatory to being used for building the walls of an extensive summer villa which he planned at this place. Thanks to the British all that is now stopped. South of the temple-tower are the impressive remains of three palaces, with great winged bulls at the gates, and many large slabs of the stone dado covered with well-preserved cuneiform inscriptions of Assurnasirpal in the ninth century B.C. Magnificent monuments from this place were taken out by early English explorers and are now in the British Museum; but nothing has been done toward recovering the plans of these palaces, or the character of their architecture. Here is a grand field for work, with the evidences of what is to be found, lying all about, leaving no uncertainty as to the returns to be expected. Several outlying mounds cover villas and outbuildings of the king, such as have been found at Assur, and distant gates in the far-sweeping lines of walls could be seen far across the city.

Nimrud (ancient Calah): The tops of sculptured, winged bulls that flanked the entrance to the palace and temple in the nortwestern quarter of the city. April 16, 1920 (N. 3008, P. 6568)

Nimrud (ancient Calah): The tops of sculptured, winged bulls that flanked the entrance to the palace and temple in the nortwestern quarter of the city. April 16, 1920 (N. 3008, P. 6568)

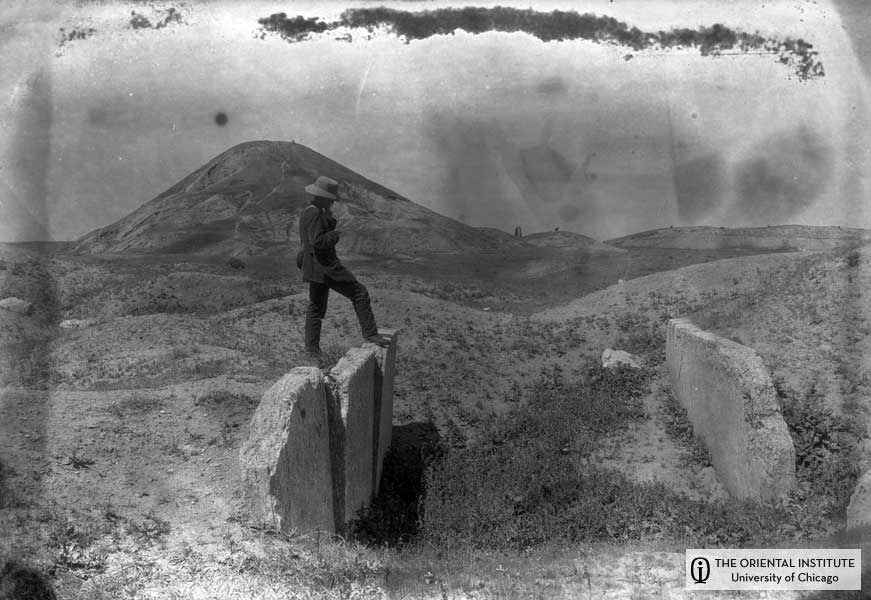

Nimrud (ancient Calah): The Palace of Ashurnasirpal III: A view looking north through the gallery which faced west. Site determined by slabs with inscriptions of Ashurnasirpal. Ziggurat in the background. April 16, 1920. (N. 3011, P. 6571)

Nimrud (ancient Calah): The Palace of Ashurnasirpal III: A view looking north through the gallery which faced west. Site determined by slabs with inscriptions of Ashurnasirpal. Ziggurat in the background. April 16, 1920. (N. 3011, P. 6571)

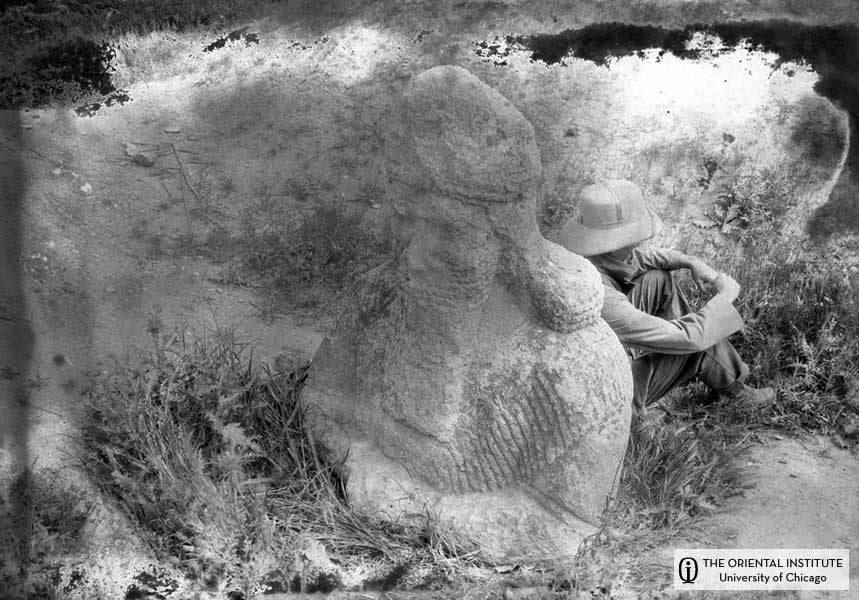

Nimrud (ancient Calah): The upper half of a buried stone statue found in the southeast corner of the ruins; the statue is facing north. April 16, 1920. (N. 3014, P. 6574)

Nimrud (ancient Calah): The upper half of a buried stone statue found in the southeast corner of the ruins; the statue is facing north. April 16, 1920. (N. 3014, P. 6574)

A drive of half an hour brought us from Nimrûd to a monastery of the old Vicar-General’s church, known as Mar Elias, which means St. Elias. We were hospitably received by the monks, and given a little refreshment which was welcome, as we had not stopped for any lunch, owing to the shortness of our time, and the grand spread awaiting us at Balawat. They showed us their old church, which was evidently several centuries old, and told us their foundation went back to the Fourth Century A.D. Driving almost due north from Mar Elias it was after four o’clock when we at length reached the Sheikh’s house at Balawat, where he had a large madhîf (guest tent) spread, with divans ranged about it after the town manner. After several rounds of coffee, followed by several more of tea, the door of the distant compound opened, and a crowd of men appeared bringing the huge tray of rice, piled high with roast mutton, with which we are now quite familiar, and also many another dish of food.

Balawat: The Sheikh’s tent with the mound in the background at the right, where the palace of Shalmaneser III was located. April 16, 1920. (N. 3017, P. 6577)

Balawat: The Sheikh’s tent with the mound in the background at the right, where the palace of Shalmaneser III was located. April 16, 1920. (N. 3017, P. 6577)

The miscellaneous display of eatables was placed on a table especially for us, and chairs were brought for all the party, except of course for a numerous fringe of natives and relatives gathered thickly about us. The walls of the big tent were raised on all sides and as it stood on an isolated hill we could see far across the surrounding uplands. A cool summer breeze played across the hill top and through the tent, while all about us was a moving pattern of nodding flowers touched with bright colors by the rapidly sinking sun. Had it not been for the lateness of the hour, it would have been a delight to linger on till the sun set. We urged the Sheikh to hasten the inevitable coffee and to finish the dinner. Nothing would do however, but that we must see his horses, a drove of thirty-five which his men now brought in across the meadow. They were fine specimens of the Arab breed, and the Sheikh went around with the greatest pride naming every strain, and telling us their qualities. It was 5:15 when we at last started across the hill tops on the long journey “home”, over not even the pretense of a road.

Just beyond the Sheikh’s house a little to the north, was the small mound of Balawat, which is on the land belonging to the Sheikh. Years ago Rassam, an oriental employed by the English to plunder Assyrian ruins for the benefit of the British Museum, dug out here the bronze mountings of a splendid pair of doors, covered with repoussé pictures from a villa of Shalmaneser IV of the ninth century B.C. They are now in the British Museum. Of course he did not clear the place, and has left us no report of its plan or character. We could no more than inspect the mound, from which without doubt much more might be taken. After a photograph or two, for we had but a few minutes, we drove on. Two miles north of this ruin of Balawat, we passed the picturesque town of Karakosh, a settlement of some 500 houses, and as the old Vicar-General told me at first it had 6,000 inhabitants, a number which he increased as his enthusiastic account of the place proceeded, to 10,000. (I learned afterward it is really 4,000!). For the place does not contain a single Moslem: the entire population is Christian, a very remarkable exception in this region. The old bishop and a number of his priests came out to greet us, and were very disappointed because we could not stop.

On leaving Karakosh our troubles began, for we had one puncture after another. Luckenbill’s immense weight makes a great difference, whether on an Arab horse or in a light Ford car, and the punctures came thick and fast. With them came also the gathering shadows, making a broken and almost roadless country nearly impassable. We were glad we had with us the Sheikh himself, who controls the tribes in this region, for we were out in a country where two British officers were murdered last December, and their bodies devoured by wild beasts before they could be found. Of one of these men, the searchers finally found a thigh bone, and a few other gruesome bits by which he was identified, but of the other man everything had disappeared. They buried one coffin with the thigh bone etc. in it, and for the funeral of the other man, (for they had a grand funeral for the two men here at Mosul), they buried an empty coffin and held the service over it. It was finally quite dark and the cars could only creep cautiously along, and the last puncture found us just entering the ruins of Nineveh, with the lights of Mosul visible across the river. We crossed the ferry in darkness, having the good fortune to find one ferry-boat still going, and when I reached the general’s house, the aide-de-camp was just organizing a search-party, and had telegraphed to the posts up and down the river in the hope of getting information of us. They seemed much relieved at our safe arrival. At dinner the general announced that he would allow us to visit Khorsabad the next day, as he now had more favorable news from the north.

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577