Wednesday Morning

April 14, 1920

We have just had breakfast at the officers’ mess and our transportation will be here in half an hour. My type-writer is mounted on a provision pannier and I am sitting on the camera trunk as I write. Through the tent door I look down across the broad river plain of the Tigris, several miles wide, probably as much as five miles in places, and extending as it does for many miles above this point, it reveals very vividly the sources of the material life on which the men of Assur depended, and which built them up for centuries while they were beginning the development of a great nation on the height overlooking this plain. I had no idea of it when I wrote about the place in my Ancient Times. All the data I had indicated that the Persian hills came right down to the river at this point. It is an indispensable element in history writing to be acquainted with the lands of which you write by actual contact with them.

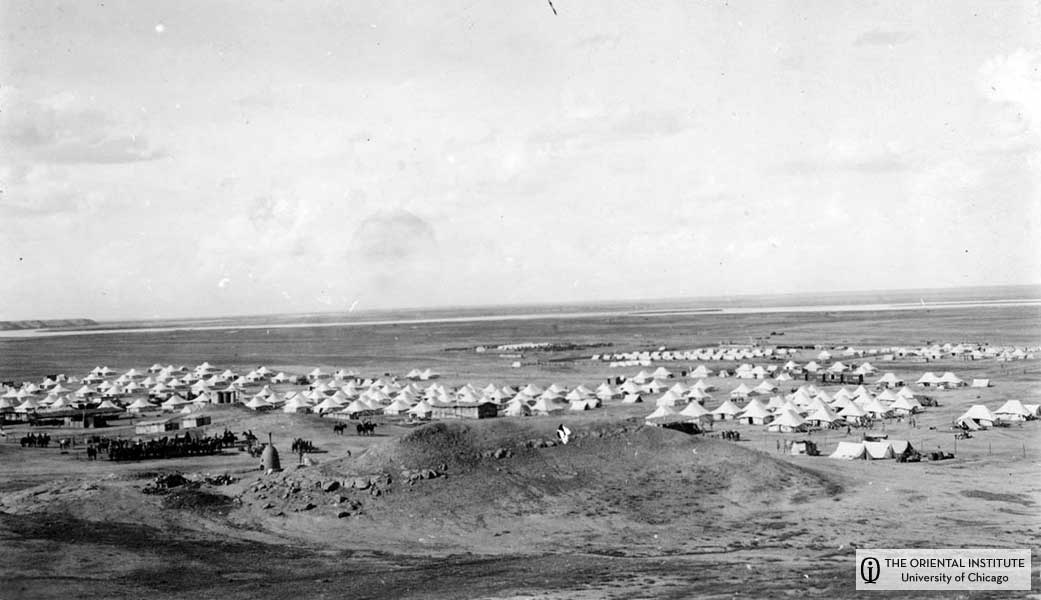

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): A view over the British camp. (N. 3671, P. 7231)

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): A view over the British camp. (N. 3671, P. 7231)

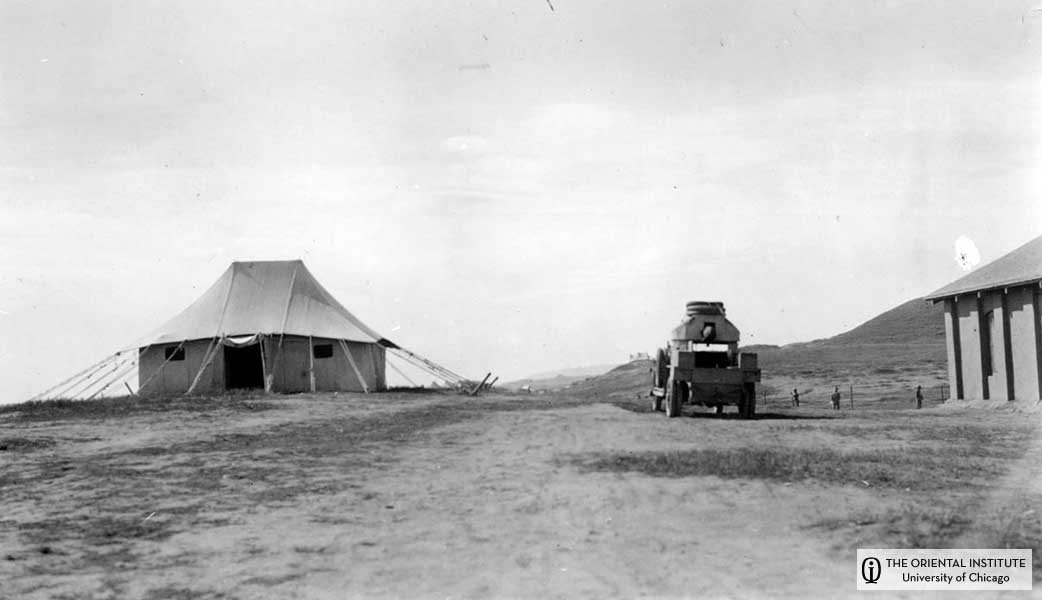

We have just been watching a long train of 125 wagons, manned entirely by Indians, deploy from the night’s camp and wind slowly away across the plain for Mosul, 80 miles up the river. Two such trains, 250 wagons in all, constantly moving between the rail head here and Mosul 80 miles up, complete the transportation link between Baghdad and Mosul. The latter place forms the northernmost limit of British control on the Tigris. Beyond that point all is entirely unsafe. We shall be able to go out to the neighboring ruins, and especially to see Nineveh; but we cannot go further. Indeed we are accompanied by escort, even between here and Mosul, and a big Rolls-Royce armored car, equipped with a machine gun, rolled in next to the mess house last night as part of the new convoy armament.

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): A Rolls-Royce armored car belonging to the British. Ashur in the background. (N. 3643, P. 7203)

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): A Rolls-Royce armored car belonging to the British. Ashur in the background. (N. 3643, P. 7203)

It will go up just ahead of us this morning. The Arabs here are not as well under control as in Babylonia, where they used to be much worse. A British major went out alone to sketch, just south of Assur a few days ago and did not return at night. The next day a searching party found his body. He had been murdered by the Arabs for what he had with him. There is no danger if people do not go out singly, but stay together. And you can rest assured we are observing every precaution. I would not write you these things, but before you read this you will have received a cablegram announcing our arrival in Egypt again; so you need have no anxiety.

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): The caravan of the Oriental Institute approaching town. (N. 3668, P. 7228)

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): The caravan of the Oriental Institute approaching town. (N. 3668, P. 7228)

We shall be glad to leave this camp, although it is very pleasantly situated. The colonel in charge is a swash-buckling, whiskey-swilling New Zealander, who made it very unpleasant at dinner last night because we refused to follow his lead in drinking. His would-be facetious jibing at our dry propensities was very offensive, and his coarseness disgusting. We were relieved to get away from the dinner table. I am now writing on my lap, sitting in the Ford car, waiting for our last car, which the young captain in charge of transport here seems to have forgotten. We sit all ready, with three vans loaded, and one touring car, but cannot move until the last touring car arrives, for the whole group must move together.

General Fraser’s House, Mosul, Mesopotamia, Wednesday Evening, April 14, 1920.

General Fraser had kindly wired General Hambro before I left Baghdad inviting me to come to his house on arriving here, and I am very comfortably put up in a large room with a sitting room partitioned off and more conveniences than are usual in this country. The house of course surrounds a large court, which in this case has been treated as a garden, with largish fig trees and a pergola. It stands on the southern outskirts of the town, at some distance from the hotel in which Luckenbill and the boys are being put up. I brought up with us an old priest who is Vicar-General of the Assyrian Church here, as one of the branches of the Oriental Christian Church is called. He is a good old soul whom I met in Baghdad. He came to call on me and described a lot of antiquities he had, and regretted he was not to be in Mosul where his home is, during our visit. He asked the American Consul to influence us to give him transportation up here, and I consented. He paid for his own ticket on the railway, or that is he paid me 30 rupees of it, and still owes me 4 rupees and 11 anas (about $2.00). I had some difficulty in securing him lodgings at the rest camp in Shergat, and this morning just as we were driving off, with the old chap in the vacant front seat beside the driver, a sergeant came running up and told me orders were that a rifleman must have room in each car. We already had one roosting on the baggage in each one of our three baggage vans, so I went up to the Colonel’s office to see what it meant. He said he had positive orders from General Headquarters to allow no car to leave without a rifleman in each car! And I must therefore throw out the old priest! I stuck and hung till the Colonel was beginning to get annoyed, and then the sergeant reminded him that there was an order also that a minimum of three rifles with each convoy was required. The Colonel looked it up, asked me if I had a revolver, which I promptly exhibited slung from my hip under my jacket, and he then gave us permission to procede. We had to wait however, for a half hour longer until three vans with mail bags, and a fourth with other luggage, joined us. As each of these cars had also its rifleman, we then had seven Indians each with his rifle perched on our nine cars. It was not until 11:00 A.M. that we at last moved off northward. Of the nine cars in the convoy, five were ours, three vans with luggage and two Ford touring cars, which however are not allowed to carry five persons out here, but only two in each seat, one of whom is the Indian driver. This limits the passengers to three in each car. Luckenbill and I were on the back seat in our car and the old priest sat with the driver in front. The general informs me that even so the road we have just traversed from Shergat is not safe. I suppose that is the reason they have brought up the big armored car we saw there.

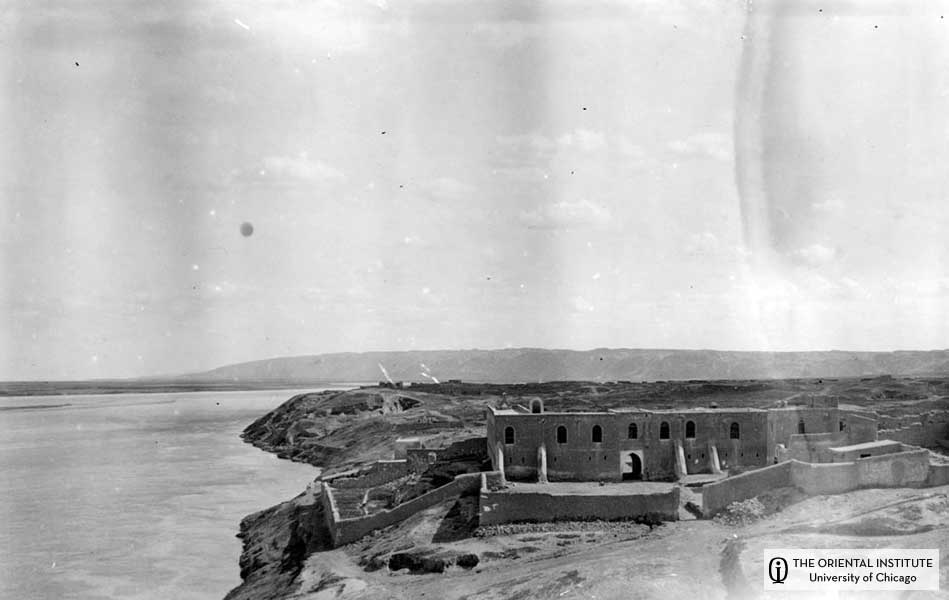

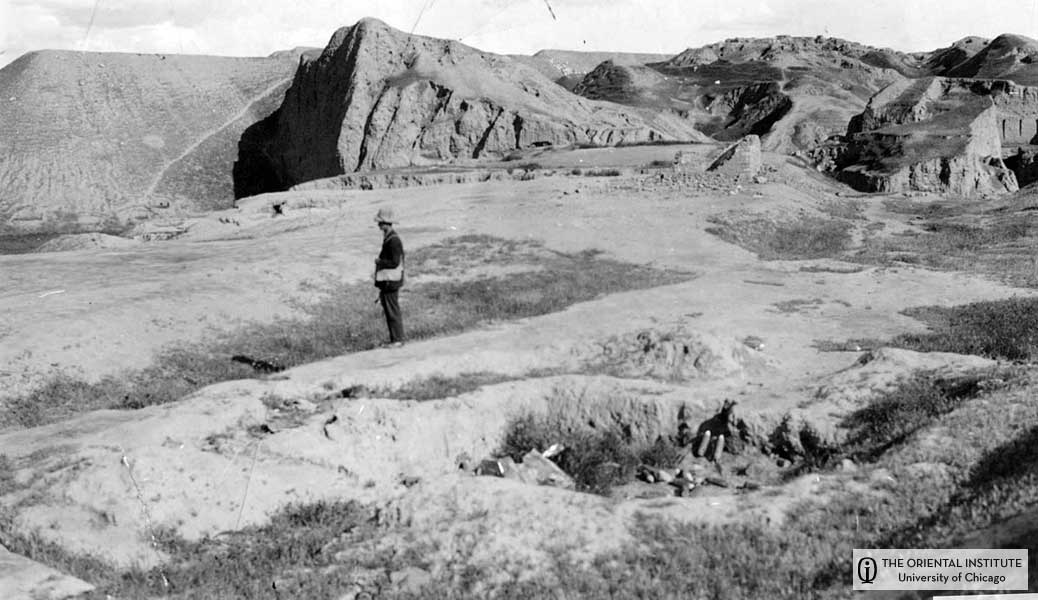

Our experiences come along so rapidly that I have no proper time to get them into a journal. We arrived as you have read above, at the Rest Camp at Shergat an hour or two before lunch yesterday. As soon as I found that transportation would not be available until today, it was evident that we must use yesterday afternoon at Shergat. There was one touring car assigned to us, which I had saved from the talons of the visiting colonel, and with this it was possible to make two trips and thus get the party five miles down the river to the old or earliest Assyrian capital at Assur, of which I have written you. Soon after lunch therefore we were off, and as we emerged from the tents we could see the ruined walls of the old city rising along the escarpment of a bold headland thrown out along the west side of the river. The road wound through the river plain upon which we looked down from our tent door this morning. The place had been completely excavated by the Germans in an uninterrupted campaign of 12 years which was completed a few months before the war broke out. It is the only place that has been completely excavated in this Assyro-Babylonian world, and the Germans have published the results in a great series of volumes which are models of what such work should be. The slopes of their great dumps are now grass-grown, but their shafts and tunnels and lateral trenches look as fresh in many places as if made yesterday. Along the northwest side of the city, protected by a large watercourse running into the Tigris, the old stone footing of the city wall may be traced for most of its length. The excavators have made long tunnels following this wall under the sun-dried brick masonry, and tracing every detail with the greatest care. Especially interesting is the northwest gate of the city with its heavy stone pavements still in place leading out across the watercourse, and supported on a substructure of large burned brick. I found blood-red anemones growing in the crevasses of this stone masonry and I enclose some of them in this letter. I followed the walls down the watercourse, and along the Tigris water-front and then climbed up into the city. Here is a large German house, looking like an Oriental fort, a big magazine building with a huge walled enclosure, and several other buildings. A large staff of archaeologists, architects and engineers had lived here. They had a launch on the river and much equipment.

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): View looking south toward house of the German expedition. (N. 3261, P. 6821)

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): View looking south toward house of the German expedition. (N. 3261, P. 6821)

No expedition ever sent to the Orient was so elaborately fitted out as this German expedition at Assur and the other one conducted by Koldewey at Babylon. Within the city the Germans had cleared and planned everything right down to the native rock where they found the oldest settlements known here in the north, — archaic remains reaching back to about 3000 B.C. All the members of the expedition were given commissions at the outbreak of the war, and served here until the collapse of the Turks. It is a crying pity that the war should have ended probably forever the most thorough and painstaking investigations ever carried on in the ancient Orient. The afternoon at this earliest capital of Assyria was to me a most instructive and impressive experience, and I hope we shall be able to go there again on our return. As we descended from the city walls to our car again we found several hundred shells lying beside excavated gun emplacements. They formed part of the Turkish ammunition supplies, abandoned when the Turks made their final retreat from the place. We made a photograph showing this Turkish ammunition with the walls and ruins of Assur in the background.

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): A view of the ruins of Ashur with modern shells in the foreground. (N. 3639, P. 7199)

Qa’lat Shurgat (ancient Assur): A view of the ruins of Ashur with modern shells in the foreground. (N. 3639, P. 7199)

When we drove out of the rest camp this morning at eleven o’clock we were therefore leaving behind the earliest capital of Assyria and making our way northward about eighty miles up the Tigris to its later and more splendid capital of Nineveh, which is just across the river from Mosul. We soon rose to the breezy and spacious Assyrian uplands, grass grown and carpeted with far reaching expanses of wild flowers in every hue of the rainbow. The most plentiful among these flowers is the deep red anemone, looking like little red poppies. The hills soon began to show plentiful outcroppings of stone, the coarse alabaster, or a variety of stone very much like it, which the Assyrians used very plentifully in finishing and adorning their palaces. Wide and impressive prospects across this hilly and broken steppe were flanked by splendid ranges of the Persian mountains rising to 10,000 feet. As we moved northward we had before us dim contours of the snow-clad range on the north of Nineveh. Four hours of driving over this highly varied and interesting country carried us at length up the slope of a massive ridge from the crest of which all at once as we rose to the highest point, we looked down upon Mosul on the west side of the winding Tigris, with the wide spread mounds of Nineveh on the opposite shore. We could follow the lines of the ancient walls including a wide stretch of grain fields and the picturesque little village of Nebi Yunus (“Prophet Jonah”), perched on the great platform where once rose the palace of Esarhaddon.

Mosul vicinity: A view looking along a modern road to the village south of the city. April 14, 1920. (N. 3646, P. 7206)

Mosul vicinity: A view looking along a modern road to the village south of the city. April 14, 1920. (N. 3646, P. 7206)

From Assur we had driven in four hours practically the whole length of ancient Assyria before it was more than a little kingdom along the Tigris for eighty to a hundred miles; and we had passed from its earliest to its latest and final capital. Every minute of the journey had been one demonstration after another in economic and historical geography of the early East. I had learned more in four hours than unlimited study of topography by means of maps at home could possibly have taught me. In a few minutes we came winding down from the ridge, as Charles will remember we once dropped from the heights overlooking Wilkes-Barre (I believe it was), though here the drop was not so great, and drove rapidly across the intervening low hills along the river to the outskirts of Mosul. Our old priest came in useful here. He showed us the way to D.H.Q. (Division Headquarters), where I found the chief of staff, Colonel Duncan, to whom the good Hambro had given me a letter. He gave us a cordial welcome and showed me General Fraser’s house, which was only two or three hundred yards from Division Headquarters. After my kit had been dumped, the old priest went with the boys to their hotel, as I have already told you.

Colonel Duncan and the general are very kind and are making all arrangements for us to visit all the important sites to be reached from here. We shall spend tomorrow on Nineveh, and then go to Nimrud, one of the earlier capitals before the rise of Nineveh and after Assur. The stone and brick bridge here has been out-witted by the river, which has shifted westward so far that it has forsaken its old course along the west walls of Nineveh and is now a quarter of a mile away from the walls. This process has carried it also out from under the bridge (a much later structure of course), so that when the river is in flood as at present, a wide and swift torrent separates Mosul from the west end of the bridge.

Mosul: The University of Chicago caravan en route to Kalat Shergat impeded by a bridge washed out by a cloudburst. April 14, 1920. (N. 3666, P. 7226)

Mosul: The University of Chicago caravan en route to Kalat Shergat impeded by a bridge washed out by a cloudburst. April 14, 1920. (N. 3666, P. 7226)

Mosul: The University of Chicago caravan en route to Kalat Shergat impeded by a bridge washed out by a cloudburst. April 14, 1920. (N. 3667, P. 7227)

Mosul: The University of Chicago caravan en route to Kalat Shergat impeded by a bridge washed out by a cloudburst. April 14, 1920. (N. 3667, P. 7227)

This interval, usually crossed by a bridge of boats, is now open owing to the strength of the current which obliges the town authorities to cut the boat-bridge until the current moderates. Hence we shall be obliged to ferry over tomorrow for our visit to Nineveh. At the same time our cars for the visit to Nimrud, day after tomorrow, will be ferried over today, so as to be available promptly when we need them.

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577