Baron's Hotel, Aleppo, Syria

May 12, 1920

Two weeks ago this morning we left Baghdad. We have come some 550 miles from the upper reaches of Babylonia, up the Euphrates valley to the heart of Syria. We have been eight days in the arabanahs, sleeping in the vile khans and knocking about all day in the rough wagons, and it would be quite impossible to try to convey the feeling of deliverance as I entered this hotel and ordered a bath! I positively think I haven’t got a flea on me; but I am one mass of red blotches from head to foot. The drivers were so anxious to reach Aleppo that they woke Ali at 2 o’clock, or rather earlier, for he called Luckenbill and me to tea at two. I heard the soldiers acting as escort tramping about over head, and what was worse, I felt them, for with every step they took, the filth and vermin from the blackened ceiling above came down in a shower on my bed. For this reason I had put up my moustiquaire. We were so glad to get away from the filthy den, that we got up, forgetting that there is an hour and a half difference in time between Baghdad and Aleppo, and we were really turning out about 12:30 A.M.!

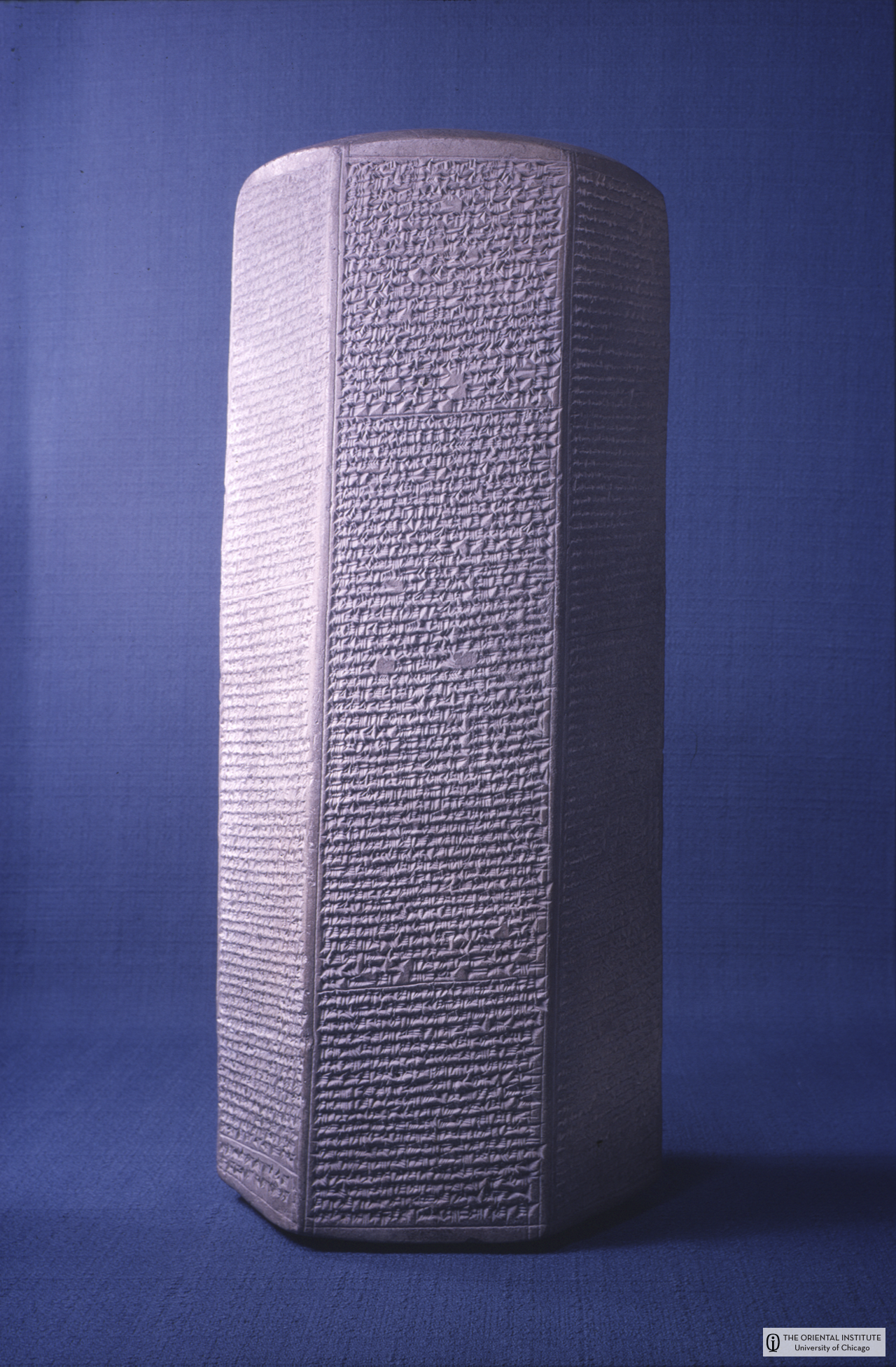

When I stepped out into the court all the other wagons were gone. The stars twinkled with marvelous brightness, while a half moon threw a ghostly light over the huge court of the khan and hanging just above the western horizon threw long broken shadows of our wagons across the litter and filth of the desolate place. All at once the place was beautiful and the spirit of the never-changing East seemed to brood over the long arcaded court of this station through which the life of the Orient had so long ebbed and flowed. A ruddy light came through the door by the main entrance, and as I stood in the silence of the night listening to the munching of the horses, the sound of voices came faintly through the open door. I peeped in and there sat our drivers earnestly talking with the khanji, which means the keeper of the khan. The scene was strikingly like some old Dutch painting of the kitchen of a wayside inn, with the coachmen gossiping with the landlord. The candle light behind them brought out in illuminated silhouette the weather-beaten features of their rugged faces, enveloped in the smoke of the cigarettes at which they puffed away with the greatest gusto. I stepped out through the great gate of the khan and looked out over the silent Syrian desert touched here and there by the fast fading moonlight. Beyond lay civilization and home, and behind me the vast Arab wilderness of the Tigris and Euphrates through which we had come. In a few hours we should be safely through it all, and then with this great adventure safely achieved, I could embark for home in a few weeks. Over there in the dark wagons was a photographic trunk filled with old Babylonian and Assyrian documents of the greatest value, — nearly a thousand of them, — with some wonderfully cut cylinder seals, some sculptures and a bronze statuette from the archaic Babylonian age, of which only a few exist. Better still, in a box by my bedside in the terrible room I had just left, was a six-sided prism of terra-cotta 18 inches high, bearing in fine cuneiform the royal annals of Sennacherib, recording among all his other achievements, the campaign against Jerusalem which called forth the great orations of Isaiah, — the very campaign on which he lost a large part of his army by a terrible visitation of plague, rendered classic in English literature by the poem “The Destruction of Sennacherib”. It cost 19,000 rupees, — nearly $9,500, but there is no monument of equal importance, — indeed no such example of royal Assyrian annals in any museum in America…

Prism of Sennacherib, now on display at the Oriental Institute Museum

Prism of Sennacherib, now on display at the Oriental Institute Museum

I have had nothing to eat since our breakfast at 2:30 this morning, except two boiled eggs, and it is now 11-1/2 hours since we had that breakfast, so I will adjourn to lunch!

Baron’s Hotel, Aleppo, Syria, Wednesday Evening, May 12, 1920, 6:30 P.M.

This noon we ate the first good food we have had for just two weeks. My [but] didn’t it taste good! After a little nap Luckenbill and I spent the whole afternoon talking first to the vice-consul, and then to the consul himself, Mr. Jackson. I can’t begin to describe to you the situation here. Even if time and space and strength sufficed, it would be altogether indescribable. The [American] consul, a very fine and experienced man, continues to reside here, though of course accredited only to the Turkish State in whose former territory he is serving. Until this territory has been formally handed over to the Arab State by the Turks, it is impossible for him to possess any legal status here at all. Fortunately the Arabs have not thought that far, and he passes informally as the American Consul here. Only 17 miles northward lies the Turkish border, beyond which are many American teachers and missionaries. They are in constant danger at the hands of the Turks. As you probably saw in the dispatches, two fine young Americans doing relief work in Aintab, not far beyond the border, were shot on the highway as they were trying to reach their work at Aintab. It is better I should not write who did it until after I am in Beyrut.

The consul has offered to help us get out to the excavations at Jerablus, the ancient Carchemish, northeast of here on the Euphrates. We left the river too far below the place to see it. He says we can do it, but there is much risk. I have decided not to take the risk for a number of reasons, though the chance is very tempting for it was one of the most important things I came to Asia to see. Furthermore, the French are just sending an expedition to relieve Aintab which has been and constantly is in great danger. Two months ago 450 Frenchmen holding the place, found themselves with only four days’ provisions and surrendered to the Young Turks on condition that they be permitted to retire to Jerablus. As might have been expected all the Frenchmen but about fifty were massacred on the way. A new French expedition failed even to reach the place during the siege, much less to relieve it; and a third expedition of 3500 men has just passed northward for the recovery of the town. This means that the Arabs will if possible cut the railroad south of here, to embarrass the French. That would cut us off from reaching Beyrut, or getting out at all without great difficulties. I have made up my mind therefore, that it is my duty to get the expedition out of such a situation as fast as I can. We are going to see the Arab governor tomorrow, accompanied by the consul, and to ask him to give us safe conduct to the great mound of Kadesh (Tell Nebi Mindoh), just south of Homs on the Orontes and then to Baalbek, which I have never seen; and finally to Rayak where we take a little cog railway across Lebanon to Beyrut. All this carries us at once into a safe region, or at least to sea connection, which will enable us to decamp when we please without hindrance from any one.

The consul says he could arrange for us to go over and see the ruins of ancient Antioch on the Gulf of Alexandretta at the northeast corner of the Mediterranean, but it is a region entirely out of control by the Arab government, and the visit would be dangerous. He could arrange to get “safe conduct” for us by putting us in charge of a bandit who lives here in Aleppo, and who has control of all the country between here and Alexandretta,—a man who has been a friend of the consul’s for years. It did not take long to cancel Antioch from our program! Tomorrow morning therefore, I shall ask the governor to get us south as fast and as safely as he can. It is evidently quite impossible to do any scientific work away from the railway leading south. We shall make the two stops I have mentioned above, and let it go at that; though not without great regret.

The consul gave us the first news of the mandates here in the Near East: Mesopotamia to Great Britain without condition; Palestine too under condition that there shall be room for a Jewish State; Syria to France; and Armenia to the United States. All this is extremely interesting when one is on the very ground. When the mandate for Armenia was first proposed for the United States, I was greatly in favor of it. But since then two important changes have completely altered my opinion. The intrusion of French control over a deeply resentful people in Syria, has plunged France into a long war with the Arabs on the south of Armenia; the grotesquely feeble and dilatory policy of the Allies toward Turkey has given the Turks the opportunity to resume their old policy of defiance all along the line, and placed another chronic war on another frontier of Armenia. At the same time the triumph of Bolshevism in Russia, which is carrying on a constant system of propaganda southward brings in a third new element, which together with the other two make it in my judgment a very unwise project for the United States to assume the responsibility for the defense and maintenance of Armenia. To police the country would require a large army, enormous funds, and a constant drain in men and resources…

You ought to hear the British officers tell of their experiences with the Armenians! How they sold to the Turks for use against the British great quantities of supplies sent for Armenian relief from the United States. I had a long talk with Colonel Duncan, chief of General Fraser’s staff at Mosul about the British dash over hundreds of miles of mountain country in response to tragic appeals for assistance from the Armenians in Baku and vicinity. When the Armenians were finally organized into a line of trench defenses, their sectors of the trenches were regularly found empty whenever the British went to look them over. Inquiry elicited the information that the Armenian officers and men were in Baku, where they might be found in the cafes! When the fighting began, one company of Staffords (British) held their position in the trenches until all their officers were killed and over half of the men. The Armenians on both sides of them had run away, allowing the Turks to cut off the heroic Staffords at both ends! And so the story went on…

For the full story of my exciting trip you should come to the special exhibit “Pioneers to the Past: American Archaeologists in the Middle East, 1919-1920,” at the Oriental Institute!

1155 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637

Hours:

- Tuesday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Wednesday 10:00 am to 8:30 pm

- Thursday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Friday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Saturday 10:00 am to 6:00 pm

- Sunday noon to 6:00 pm

- Closed Mondays

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/special/pioneer/

And visit me on facebook at: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=3318774#/profile.php?v=info&ref=profile&id=100000555713577