Recently in Behind the scenes Category

Theaster Gates shows how creating intentional space for community can drive artistic discourse, through the construction, layout, and use of the Dorchester Projects house, home to the Soul Food Pavilion dinners.

An open bar, and a lively crowd past closing time - are you at a gallery opening? A happy hour? Or simply enjoying beer with friends?

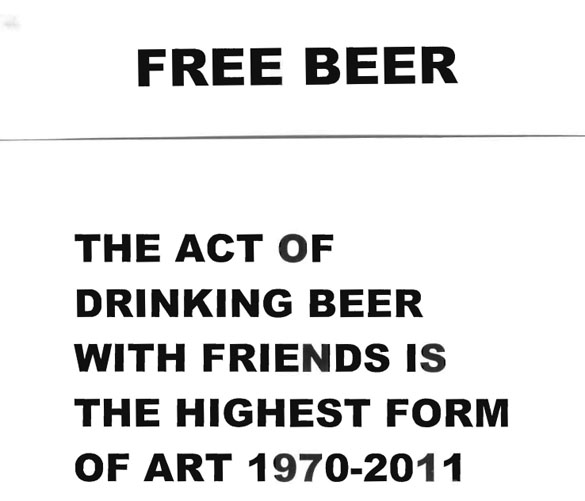

Describing his long-running salon, The Act of Drinking Beer With Friends Is The Highest Form of Art - staged throughout the world since 1970, always in accordance with specific guidelines - Tom Marioni quotes Benjamin Franklin: "Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy."

The popular Feast fixture returns this Thursday with special guest bartenders, members of the Chicago hip-hop collective BBU. Upcoming bartenders include poets and teaching artists from Young Chicago Authors and experimental theater collective The Neo-Futurists. Keep an eye to our Facebook events page for updates.

The evening served as a preliminary training for student staff in how to serve the slatko to museum guests once Feast opens. It was also a chance to sample the batch of slatko that a crew of Smart Museum staff members (and Stephanie's mother) prepared for Ana's project this past summer. Eyes widened as students tried spoonfuls...

The consensus was overwhelming that the slatko is very, very sweet.

By Breck Furnas

Education Program Coordinator, Smart Museum of Art

Preparing a meal and sharing it with family was how my great-grandmother maintained bonds with those closest to her. She was born into a large family of laborers in rural Kentucky where one of the only opportunities to communicate and show affection to loved ones was at the dining table. Her homemade biscuits, bread, and jams bore the signs of her love as well as a lifetime of hardship. Nothing went to waste. Her creativity was sparked the most when she had the least.

I was fortunate enough to be the beneficiary of many inventions -- not limited to just food -- being raised by my great-grandmother. Not everything was a success. I distinctly remember once eating cookies made with stale Fruity Pebbles, but I miss those strange failures as much as her delicious pies.

Developing and managing family programs at the Smart the past year and a half has allowed me to tap into her skill set -- making connections between seemingly disparate concepts for the enjoyment (hopefully) and education of others. There's always a bit of a challenge in effectively relaying information from heavily researched and scholarly exhibitions to a five-year old, but believe you me their observations will give you plenty food for thought. For the Family Day tied to Feast, I've worked closely with John Harness, Education Intern, in thinking through the art activity in our lobby (we also have performance and visual art workshops, gallery activities, etc.):

BF: I think it was your idea to do a still-life collage, right?

JH: Right. We try to make direct connections to specific art pieces in our collection for all the programs we do, and the photographs of food and dinner tables by Laura Letinsky that will appear in Feast really stood out as something we could approach with kids. It's hard to do photography in this sort of setting, but I thought we could touch upon things like color, shape, and composition (which are so central to Letinsky's work) through the more kid-friendly medium of collage.

After all, kids everyone loves glue-sticks.

BF: Yeah, we've done photography workshops in small groups, but it demands a structure that's not possible with around 100 family members in the lobby of the Museum. Considering not only the artwork but the themes of sharing and mutual exchange in the exhibition, I wanted to connect (as I try to with all family programs) the "Four C's of 21st Century Education": creativity (creating new ideas, refining and evaluating ideas, etc.), collaboration (being open to diverse perspectives,viewing failure as part of the process, etc.), critical thinking (making complex choices and decisions, understanding the interconnections of systems, identifying and asking important questions that lead to better solutions, etc.), and communication (articulating ideas clearly and effectively).

I wanted to think of a way to bring the still-life into this contemporary educational practice -- through something communal. The kids create shapes or silhouettes of food for themselves and others to use. They'll be encouraged to think about their memories of favorite shared meals or what they like to eat with their families.

JH: It's always challenging to get the kids to share; I'm sure no one reading this will surprised by that! As you've just mentioned, riffing on the idea of radical hospitality, we especially want to emphasize collaboration and sharing for the Feast family activity. We haven't got the kinks worked out of this plan yet, but the idea is to get the kids to share a limited supply of materials so that they will have to consider reusing and re-purposing what they might otherwise think of as someone else's scraps. (Usually each participant gets a "new, clean sheet of paper," so to speak. Not so in February!) Obviously there are important messages about environmentalism and recycling that can be read into this as well, and I hope kids will pick up on that. Maybe I'll be able to get a few of the kids to start making cut-outs specifically for others to use, but they can often be pretty protective of "their" creations. So, I'll have to see how that plays out.

BF: I think you said the phrase "economy of paper" at some point. Kids can go to great lengths to safeguard what they feel is their personal possession. They also can sometimes have an eye for the prized possessions of others. Sharing (and by extension collaboration) is a huge lesson for our typical age group (4-7 years). They'll be encouraged to help others by donating some cut-out images if they choose to take any of the communal cut-out images out of a shared bin. Art education offers so many levels of instruction (and life lessons)!

Do you know what would be in your collage? Any favorite family meal?

JH: Hah. Well, I'm torn. You and I have a lot in common because I've spent a lot of time with my grandmother and her amazing Southern cooking -- that whole side of the family is from Alabama and I'd love to make a collage with okra and green tomatoes and Grandma's funky plates from the '70s. On the other hand, my other grandmother came from a Wisconsin Norwegian background and there are a lot of great ethnic foods that we would always eat around this time of the year. We'd have things like weirdly-shaped cookies with names like krumkakes and sandbakkels and pepperkakens, and a huge flatbread called lefse. I'd love to make a collage with all those things.

Maybe I'd make some sort of Southern/Norwegian "fusion" and make a collage with lots of krumkakes filled with okra or lefse and kudzu leaves. Then it'd be something like a self-portrait, in a way. I think it could be really neat to hear kids talk about their families, especially if they are aware of their extended families and food traditions connected to their heritage.

By Angela Steinmetz

Head Registrar, Smart Museum of Art

For a museum collections manager or registrar, food in the galleries can pose some big problems. There is a reason most museums strictly ban food and beverages in their galleries, mainly due to the risk it poses to their collections. There is the obvious damage that may happen if food or drink is spilled directly onto artwork, but there is also the increased risk of pests (insects or vermin) that are attracted to food also being attracted to various parts of artwork -- and I'm not talking about appreciation of the art for its visual presence! Certain bugs find wood, paper and textiles very tasty and we try very hard to keep them away from the collections we want to preserve.

So, what happens when your whole exhibition revolves around art made of food?

For Feast, we are taking some extra precautions to make sure our art doesn't invite the wrong kind of audience. For instance, the fresh food used for Alison Knowles's Identical Lunch will be placed in a closed container in the gallery -- not out in the open -- so that it will be less of an attraction to any pests that may come in from the outside, and minimize the risk of elements of the meal accidentally spilling onto other artworks in the gallery.

Ana Prvacki's The Greeting Committee and participatory elements of Mella Jaarsma's I Eat You Eat Me will be presented in our lobby instead of the galleries because they involve guests consuming food. We will also segregate our Bernstein Gallery from the rest of the galleries at certain times in order to present Tom Marioni's The Act of Drinking Beer With Friends is the Highest Form of Art. There will be several events over the run of the show where the gallery will become an active bar with patrons taking part in the work by drinking beer.

One of the most challenging pieces in terms of keeping the pests out will be Lee Mingwei's The Dining Project. The artist will be serving meals to a select few individuals during the run of the exhibition in the gallery space. We don't want any crumbs or left-overs to attract pests, so we will be performing thorough cleanings of the area after the meals take place, and will be continuously monitoring the space with small bug traps so that we can address any issues that may arise.

The Dining Project also incorporates 270 pounds of dried black beans into its large platform -- yes that's a lot of beans! Before the beans even enter the galleries we will need to make sure they don't contain any bugs. This can be done by "cooking" the dry beans at a low temperature in an oven, or alternatively the bugs can be killed by freezing and thawing the beans over several weeks. The freezing trick is often used by museum professionals to control bug infestations (it is usually less damaging to objects than heat), but the Smart has utilized the faster heating method for contemporary projects where the materials end up being discarded after the exhibition. The full-sized tree used in Guy Ben-Ner's Wild Boy, shown in the Smart's presentation of Adaptation in 2008, was heat treated in an industrial wood kiln in order to make sure that it did not contain any art-eating bugs, and was also safe for the public to touch.

The Dining Project also incorporates 270 pounds of dried black beans into its large platform -- yes that's a lot of beans! Before the beans even enter the galleries we will need to make sure they don't contain any bugs. This can be done by "cooking" the dry beans at a low temperature in an oven, or alternatively the bugs can be killed by freezing and thawing the beans over several weeks. The freezing trick is often used by museum professionals to control bug infestations (it is usually less damaging to objects than heat), but the Smart has utilized the faster heating method for contemporary projects where the materials end up being discarded after the exhibition. The full-sized tree used in Guy Ben-Ner's Wild Boy, shown in the Smart's presentation of Adaptation in 2008, was heat treated in an industrial wood kiln in order to make sure that it did not contain any art-eating bugs, and was also safe for the public to touch. The museum is taking extra precautions for the artwork that will be presented in Feast, but museums all over battle with pests daily in their work to preserve art and artifacts for future generations. Most museums practice some form of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in order to safeguard their collections -- ranging from pest monitoring and special cleaning schedules, to the ever-present no food and drink policy.

So the next time you want to bring your coffee into the museum but find yourself staring at a "no food and drink" sign, don't be disappointed. Take some pride in knowing that you are helping to protect the museum's collections from damaging pests instead!

Top: Lee Mingwei, The Dining Project, 1998, documentary photo of performance at the Whitney Museum of Art. Courtesy of the artist and Lombard-Fried Projects.

Above: The tree used for the Smart's 2008 presentation of Guy Ben-Ner's Wild Boy was heat treated to make sure it was pest-free.

By Alice Kain

By Alice KainStudy Room Supervisor, Smart Museum of Art

Theaster Gates is currently collaborating with three Japanese potters as part of his Soul Food Pavilion project for Feast. The potters recently travelled to Chicago to make dishes for the soul food ceremonies, which will be held at Theaster's Dorchester Project.

On their recent visit to Chicago the potters, Kouichi Ohara, Haruka Komatsu, and Yoko Matsumoto, were able to spend time with some of the ceramics in the Smart Museum collection. The potters, and Theaster's assistant Marlease Bushnell, were shown examples of Korean ceramics chosen for them by Richard Born, Senior Curator at the Smart. They were also shown a selection of Classical Greek ceramics by Richard Neer, Professor of Humanities and Art History at the University of Chicago. This combination provided an interesting juxtaposition of the familiar --Kouichi was especially knowledgeable about the 12th century Korean pieces-- and the unfamiliar, particularly with the methods used by the Ancient Greek potters. Initially the visit had been scheduled to take place in the Smart museum study room, but the number of ceramics to be shown became far too large for this space! The museum holds a culturally wide and valuable collection of ceramics, many of which are kept in storage and mainly used for research purposes. It was in this museum storage area that the potters were to have an up close encounter with some of these pieces. The potters were excited to have the opportunity to see the dishes and bowls without a glass vitrine.

Richard Neer provided an excellent narrative to the Greek pottery on display, explaining the particular method of clay slips and low oxygen firing that produced the familiar black and red figure glazes. A highlight was Richard's demonstration of a popular Greek drinking game. Using the Dionysus wine bowl as an example, he showed the potters how the Ancient Greeks would swirl the last dregs of wine in their cups and then throw them at a target on the wall! The Dionysus bowl particularly caught the potters' imaginations, as the painted eyes on the underside of the cup would have provided a facial mask for the drinker, referring to the God's role as patron to drama as well as winemaking, and also referencing the drinker's mask of inebriation.

After the visit Marlease reported back that Kouichi was particularly honored to have spent time looking at the Korean objects in storage: "Those pots were talking to me, and I would need to spend a whole day with them to hear all that they were saying."

Image: Kouichi Ohara, Haurka Komatsu, Yoko Matsumoto, and Richard Neer examining pottery from the Smart's collection. Photo by Sara Patrello.

By Jenn Sichel

University of Chicago PhD student and Smart curatorial intern

This fall, I met with Tom Marioni to make plans to drink

beer.

Below you can see a few of his very detailed plans for his

installation of The Act of Drinking Beer With Friends is the Highest Form of

Art. As a part of Feast, the Smart Museum's

Bernstein Gallery will be transformed into a space for drinking free beer with

friends -- replete with a bar, table, refrigerator, yellow lighting, and a shelf that will hold

exactly 8 cases (192 bottles) of beer.

The studio and classroom spaces of the historic Lorado Taft building of the University of Chicago's Midway Studios are like attics in an old house. They are lofted and beamed, and in this transitional year as the department prepares to move into the Logan Arts Center, piles of supplies and debris stand both as monuments to the logistics of moving, and, last spring, of classes preparing for finals. Stacks of paper covered surfaces, corners of rooms cluttered with charcoal, wire, and foam; underneath a staircase was a neat pile of deconstructed electrical appliances. In another incarnation, the room where Stephanie and Laura's Food for Thought class met last spring could have been a Victorian sitting room, with bay window and lavender-painted molding. As is, a couple of tables pushed together take up most of the room, and on the day of Michael Rakowitz's visit, these were taken over by ingredients: peppers, onions, bags of lentils and rice, bottles of oil and spices, ground beef, hot plates, and glass cutting boards bearing Michael's Enemy Kitchen logo.

The studio and classroom spaces of the historic Lorado Taft building of the University of Chicago's Midway Studios are like attics in an old house. They are lofted and beamed, and in this transitional year as the department prepares to move into the Logan Arts Center, piles of supplies and debris stand both as monuments to the logistics of moving, and, last spring, of classes preparing for finals. Stacks of paper covered surfaces, corners of rooms cluttered with charcoal, wire, and foam; underneath a staircase was a neat pile of deconstructed electrical appliances. In another incarnation, the room where Stephanie and Laura's Food for Thought class met last spring could have been a Victorian sitting room, with bay window and lavender-painted molding. As is, a couple of tables pushed together take up most of the room, and on the day of Michael Rakowitz's visit, these were taken over by ingredients: peppers, onions, bags of lentils and rice, bottles of oil and spices, ground beef, hot plates, and glass cutting boards bearing Michael's Enemy Kitchen logo.In many ways, the character of Michael's spread matched that of Midway's material sprawl: an idiosyncratic combination of bought and found, hunted, gathered, and on loan, as if part of a work-in-progress. As Michael introduced us to the ingredients and his recipes we prepared together for our lunch, he described how creating a migratory cooking space can also be a rhetorical strategy. Setting up these somewhat impromptu, collaborative cooking sites, as he has in his Enemy Kitchen project, becomes a way to forge an inclusive role for himself as artist, teacher, and cook, as a facilitator: the one who starts bringing all the necessary elements together so that the rest of the experience can unfold. In order to make our lunch, we borrowed pots from one student and a hot plate from another; in between stages we ran bowls down to the nearest sink in the basement bathroom to be washed.

Both in previous iterations of Enemy Kitchen, and in his project for Feast, Michael has been interested in developing a form to reflect the multi-dimensional processes of cultural exchange. His project utilizes the capacities of cooking and eating to foster sites of exchange, while also using them to foreground and refute the general absence of Iraqi cuisine from American consciousness. In this way, Michael's project provokes questions about what we have access to and why or why not: about how to exchange that which we don't seem to be able to exchange. The bought ingredients and borrowed supplies function as he does, as facilitators. In Michael's practice, cooking becomes a means of facilitating another kind of practice: that of recognizing and expressing our embedded relationships to Iraq, to nationality, to family, to media consciousness, and to war. At lunch last spring we talked about Michael's plans for his food truck project for Feast. As those plans become more actualized over the next few weeks and months it will be interesting to see what roles cooking and eating develop, and how the logistics of dealing with Chicago food truck regulations becomes another kind of facilitator.

Over the last century, artists have often sought to break down the boundaries between art and everyday life--and the Smart just acquired a work of art by the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri (b. 1930) that exemplifies this way of working.

Over the last century, artists have often sought to break down the boundaries between art and everyday life--and the Smart just acquired a work of art by the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri (b. 1930) that exemplifies this way of working. In the early 1960s, Spoerri pioneered a practice that he later defined as "Eat Art." As the name implies, much of Spoerri's art centered on meals: in addition to writing and making more traditional drawings and objects, Spoerri staged banquets and created restaurant-art-projects such as the fabled Restaurant Spoerri and adjacent Eat Art Galerie in Dusseldorf. These hubs of artistic experimentation and social pleasure attracted leading members of the European avant-garde art community as well as the general public. They were also sites where Spoerri created some of his famous "snare pictures," for which the remains of an actual meal were affixed to a table and then turned sideways to create an object that hangs on the wall like a painting. A kind of readymade still life, the composition was determined by chance--the residue of consumption and convivial interaction rather than aesthetic intention.

While researching Feast this past spring, I discovered that a classic, abjectly beautifully Spoerri snare picture--made at Eat Art on June 17, 1972--was at a Swiss auction house. The Museum was successful in acquiring it and, as a result, the Smart is now one of the few US museums to own snare pictures (along with the Walker Art Center and the Museum of Modern Art). The work will be a centerpiece of Feast along with a rich selection of other material by Spoerri.

After Feast's national tour, it will return to campus as a lasting resource for research and teaching--and, we hope, an inspirational example of how artists can make powerful works out of common experiences.